Volocopter says eVTOL technicians will need to be jacks-of-all-trades rather than system specialists.

In less than a year, the aviation industry could see the first service entry of an advanced air mobility platform. Volocopter is targeting mid-2024 for its VoloCity electric vertical-takeoff-and-landing air taxi, and Joby and Archer are not far behind, with expected service entries in 2025. With these dates approaching rapidly, will there be enough time to develop the necessary technician training framework for servicing the platforms?

Many advanced air mobility (AAM) OEMs have spoken generally about plans for maintaining their aircraft, and most highlight maintenance simplicity as a selling point. However, even simple aircraft need certified technicians to keep them flying safely.

Volocopter, which plans to submit its formal application for Part 145 Maintenance Organization Approval this year as part of its aircraft certification efforts, notes that it is working on developing a training program that will comply with European Union Aviation Safety Agency regulations. Oliver Reinhardt, Volocopter’s chief risk and certification officer, says the company does not expect technician training to be “hugely different” from commercial aviation MRO, but there are differences that will need additional focus.

“Any eVTOL [electric vertical-takeoff--and-landing aircraft] will require a skilled technician to handle high-voltage batteries safely, and in the Volo-City’s case, swiftly swap the battery at vertiports. This is a novel aspect where we are developing these required skill sets jointly with the respective authorities,” he says. “Since the technology of an eVTOL is still a novel concept, special focus will be on avionics, flight controls, electrical wiring interconnection systems and composite materials for all technicians.”

While maintenance will be simplified because Volocopter’s aircraft designs have significantly fewer moving parts and no fluid or fuel systems, Rein-hardt says technicians who work on these aircraft will need to be generalists for all technical ground operations instead of specialists in specific systems, given the different maintenance model they will require.

“From a logistical standpoint, vertiports in cities will have restricted space and much faster aircraft turnaround times,” he says. “In comparison to general commercial aviation, there will be far fewer technicians working on one aircraft, which means that one technician will need to know the ground operations of the aircraft, with multiple tasks assigned to them. An eVTOL technician will have to understand the complete aircraft and its system design because they will be working on location in small teams.”

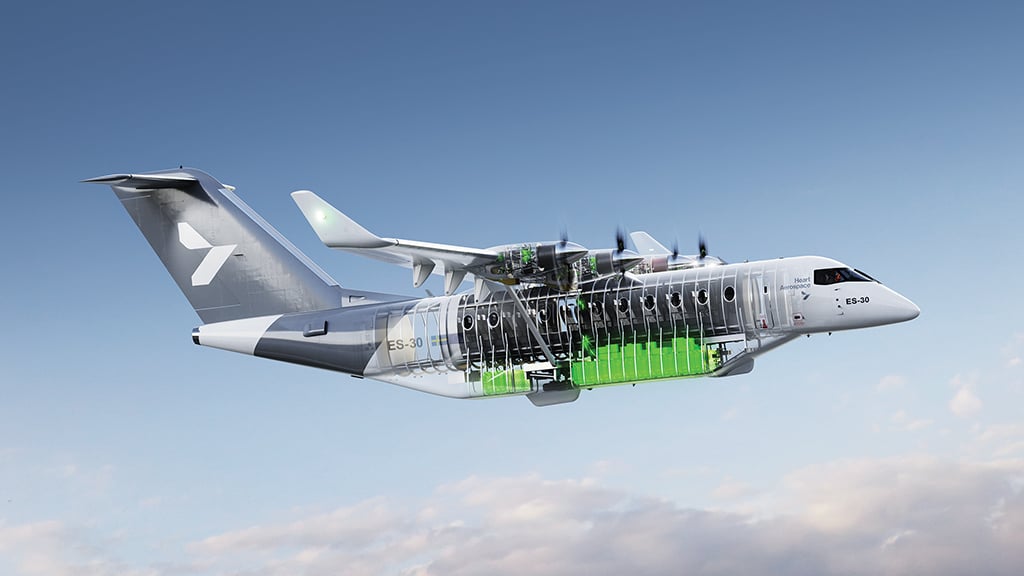

Other electric aircraft OEMs share similar perspectives about the skill sets AAM technicians will need. A representative for Beta Technologies notes that an understanding of carbon-fiber composites and electric propulsion systems—including high-voltage distribution, inverters and electric motors—will be critical. Simon Newitt, chief commercial officer at Heart Aerospace, says the company is designing its ES-30 hybrid-electric aircraft with a “conventional approach as much as possible,” so the biggest difference will be around the propulsion system.

“When we’re thinking about the technician training, we’ll see a very familiar syllabus being put together,” Newitt says. “The differences are really going to be around that battery. These are much bigger batteries.” He notes that the ES-30 will feature 5 tons of batteries. “So how do these batteries come off the aircraft? You’ve got implications on [center of gravity],” he says. “Maybe some new ground support equipment will need to be evolved to cope with this because of the weight.”

PREPPING SCHOOLS

Jared Britt, director of global aviation maintenance training at Southern Utah University (SUU), says aviation maintenance schools that teach avionics already have most of the building blocks to teach these types of AAM skills. “This isn’t a huge leap, and I think we get caught up with these buzzwords of emerging technology and eVTOLs,” he says. “The technology is a huge leap, but the ability of a person to repair that technology and the knowledge that they need are not that huge of a leap.”

At Northland Community & Technical College in Minnesota, which already has a robust uncrewed aircraft systems (UAS) program, last year’s update to the FAA’s Part 147 maintenance training curriculum has been an opportunity to revise courses with a heavier focus on electricity and composite structures. Zackary Nicklin, UAS program manager at the college, says merging UAS skills with those of a traditional aviation maintenance technician (AMT) will help better prepare graduates for the aviation industry in general.

“UAS has really relied heavily on sensors, data links, computers and networking, which is all stuff that we’re seeing in manned aircraft these days,” Nicklin says. “When you go on a new [Boeing] 787 or [Airbus] A380, everything is connected through digital electronics—it’s data buses rather than rigging and cables.”

Stephen Ley, associate professor in the School of Aviation Sciences at Utah Valley University, has been working to propose a training concept called Part 147+, which would enable schools to “bolt on” courses within their aviation maintenance training programs that would give students opportunities to specialize in AAM, similar to the way students can now specialize in avionics.

“Because of converging technologies, there are a tremendous amount of common skill sets that overlap and are fulfilled by the existing Airman Certification Standards, so why reteach it? [You can] just integrate it and have a bolt-on program,” Ley says. At schools that already offer adjacent technical programs, such as automotive technology, he suggests synergies could be found in areas like electronics. “These are adjacent technologies, so why treat electron theory differently across multiple disciplines and duplicate courses, labs and capital equipment?” he says.

Ley and Nicklin have begun collaborating to host EVPro+ training for instructors at their schools, which focuses on electric vehicle fundamentals and safety for a variety of industries, such as automotive. “The idea is to get aviation educators up to speed on high-voltage electric propulsion distribution and storage systems, with the intent that we can start building some of that into our AMT programs as well,” Nicklin says. “Being able to give the students the foundational building blocks to then take OEM information and actually apply it without starting from zero is kind of the concept.”

DATA HURDLES

However, accessing data from OEMs is still a major roadblock for most schools. “The proprietary nature of the emerging technology is a problem,” SUU’s Britt says. “People aren’t going to want to share what they’re building with us.”

Tracy Yother, assistant professor of aeronautical engineering technology at Purdue University, says procuring information from AAM OEMs is the biggest challenge for educators who want to train students in these emerging technologies. “This happens every time we get a new technology, when people who are developing it are nervous,” she says. “They’re trying to be ahead of the curve so they can bring something new to the market. Because of that, there are some nerves in sharing information. For us to prepare the technicians, we have to know what the system is about.”

Yother stresses that schools do not need proprietary information but rather the basic theory of operation to understand how to deal with key aspects of the aircraft, such as high-voltage systems. “In aviation, we’re not used to dealing with high voltage, so we’re going to have to teach our students how to handle that. The best we could do is pull from ground vehicles and cars,” she says. “We’d much rather have the information from the people who are manufacturing the aircraft, telling us: ‘We’re running 800 volts through this at times. Here are the points you don’t want to be touching.’ Those points are going to be different points than what are found on a car.”

For now, Yother and other AMT instructors are relying on adjacent technologies or incomplete information to build training courses, which is not ideal. “Right now, if you’re building a course, you’re pulling from what’s out there on the internet” she says. “Every time one of these companies has an interview with a journalist, they give little pieces of information. It’s a combination of the internet and what we know from other industries such as automotive that we can pull in.”

From the OEM perspective, Heart Aerospace and Volocopter both argue it is still too early to share aircraft data because nothing has been certified yet for commercial use. “In this fluid situation, it will be undoubtedly difficult to share everything with others if the aircraft has the possibility to change,” Volocopter’s Reinhardt says.

“We are transparent as much as we can be,” Heart’s Newitt says. “We want to collaborate, and we’re looking for universal application. We don’t want to develop customized, specific, tailored solutions that only are applicable to the Heart Aerospace aircraft. We want to address the market requirements as universally as we can because our mission is to help this industry transform itself sustainably.”

IN-HOUSE TRAINING

In the interim, companies may be most likely to keep technician training in-house. “These companies should look at building training programs that have proprietary information, just like Boeing does,” Britt says. “If you go to work for Boeing, you spend a couple months in training, and everything you learn is proprietary to Boeing. They do that so they can make sure they have exactly the person that they want. I think that’s what your [AAM OEMs] are ramping up to do.”

Heart Aerospace is still in the process of deciding how to structure maintenance training. Newitt suggests the most likely solution will involve partnering with a third party. The company is in the beginning stages of reaching out to local educational partners to “develop local solutions where a market calls for it,” Newitt says. Volocopter is also in discussions with potential training partners such as the Institute of Technical Education in Singapore.

“As the industry scales, these skills will increasingly be part of curricula at A&P [airframe and powerplant] schools, but initially, it will be up to OEMs to build relevant maintenance training for both their own technicians and mechanics, as well as their operators,” says a representative for Beta Technologies. “We’re putting a lot of thought into what this looks like, both for our own Beta team and for our customers, like UPS and Bristow.”

Nicklin acknowledges the constraints of early-stage aircraft certification but cautions that relying solely on internal technician training could come with challenges.

“The reality is that as soon as these organizations start getting the larger contracts, they’re very quickly going to wind up in one of two places,” he says. “One is they’re going to be paying engineers to do technician-level work, which in my mind is not a great business model. Or they’re going to be taking people off the street and training them up, which has its own hazards when we talk about aviation, because aviation maintenance is absolutely a mindset around safety culture that you don’t always see from other professions.”

While OEM collaboration is on the road map, Ley points out that AMT educators must be proactive rather than waiting for the FAA to develop advanced air mobility technician training standards.

“We need to look at a [1-10-year] perspective when it comes to emerging technologies. It’s why the FAA gets behind—because we’re reacting instead of being proactive,” he says. “We see a train wreck coming, and if we don’t react right now, then we’re going to be behind. We see the technology in front of us, and we can forecast the likely impact that technology will have upon our current A&P technician standards. Intrinsically, we can see there’s a gap. What are we going to do to fill that gap?”

All of the educators interviewed by Inside MRO are involved in multiple industry efforts to develop an AAM curriculum and standards. Some examples: a Clemson University proposal to NASA for a research project to investigate the challenge of developing AAM maintenance technician standards, which will feed into the FAA; a National Science Foundation grant to build a curriculum and train MROs; a collaboration with the Society of Automotive Engineers on how to create certification standards for aerospace; and Utah’s Advanced Aviation Maintenance Planning Working Group, which meets with companies to talk about developing standards.