A graphic of the European Union depicts the various new regulations that affect business aviation.

Business jet operators flying to the UK and Europe must navigate through an increasingly dense thicket of taxes, travel authorizations and emissions tracking and sustainability requirements.

“As these requirements keep bubbling up, we’re going to see more enforcement action,” said Adam Hartley of Universal Weather and Aviation, speaking Feb. 13 at the NBAA International Operators Conference (IOC2025). “If we’re at 50 [countries] globally now that require electronic transmissions before you go, in another five years we’ll be at 100.”

The mostly Part 91 private jet operators and pilots who attended IOC2025 will not be affected by the steep increase in passenger taxes that France will charge commercial and charter operators flying from French airports as of March 1. But France and several other European countries, including Austria, Belgium, Germany and Portugal, do collect fees and taxes from private aviation. The UK will increase its Air Passenger Duty in April 2026, elevating the maximum per-passenger rate to £1,000 ($1,260).

Last April, the UK updated its General Aviation Report (GAR), a submission required of “owners or agents and captains of GA aircraft” making international flights to and from the UK, Ireland, the Isle of Man and Channel Islands. Information about a flight and its crew and passengers must be submitted via an online portal or third-party app no earlier than 48 hr. and no later than 2 hr. prior to the expected departure.

Fines of up to a £10,000 will be assessed for inaccurate or incomplete GAR filings. Some 240 warnings have been issued in last six months, Hartley said, but fortunately only one penalty resulted.

As of Jan. 8, travelers to the UK from North and South America need an electronic travel authorization (ETA) costing £10, which is valid for two years. As of April 2, ETAs will be required from other nationals. This applies to active or positioning flight crewmembers, Hartley said.

New travel fees and authorizations tie into evolving electronic filing requirements. Hartley serves on the Working Group for Carriers of eu-LISA (the European Union Agency for the Operational Management of Large-Scale IT Systems in the Area of Freedom, Security and Justice), a multi-phase program that involves the development of an electronic travel authorization and pre-validation of short-term visas for people traveling to the EU.

The carriers’ group is working to facilitate the use of automated systems—the European Travel Information and Authorization System (ETIAS) and Entry/Exit System (EES)—by air, sea and motorcoach carriers.

“It’s going to affect exit/entry processes on the ground,” Hartley said. “It will affect your pretravel electronic manifest and how you schedule and what you’re transmitting and what your travelers are required to have before you get into the zone. You’re not transmitting your visa information, you’re transmitting your name, date of birth, passport number—and the system is going out to the member states, finding your visa in the system and returning an interactive go or no-go.”

The eu-LISA program missed a November 2024 implementation target and is now formulating a “progressive” schedule to introduce carrier interfaces to the automated systems.

“We’re going to see a varied implementation,” Hartley said. “That’s going to be really challenging because each member state is going to be given a little latitude to change their processes slowly, to run duplicate processes.”

He added: “We’re concerned about it. Obviously, we run a smaller manifest load—smaller groups of travelers. The airlines are very concerned about this and how they control their air travelers and what they’re able to do.”

Starting this year, aviation fuel suppliers at EU airports are required to blend a minimum of 2% sustainable aviation fuel (SAF) with conventional jet fuel under the ReFuelEU initiative, a share that will increase to 70% by 2050. The SAF mandate applies to all commercial and private flights departing EU airports.

To discourage the practice of “tankering,” or carrying excess fuel to avoid refueling at destinations with higher fuel prices, the regulation mandates that operators uplift at least 90% of the required fuel for flights departing from a specific EU airport at that airport.

“ReFuelEU is mandatory implementation—pressure—for operators to utilize SAF, for ground handlers and airports to have SAF available for you to use, [and] to discourage things like tankering,” Hartley said. It exerts “a lot of pressure on the [SAF] market for business aviation, for the airlines, for everybody, to meet some of the aggressive [emissions] mandates they’ve put out.”

Sustainability metrics related to emissions trading schemes are expanding by taking into account non-CO2 emissions, including water vapor and particulates leading to contrail formation, Hartley said. “Non-CO2 effects need to be added to your monitoring plan,” he advised. “There will be templates [available] for what we’re going to be using as small emitters.”

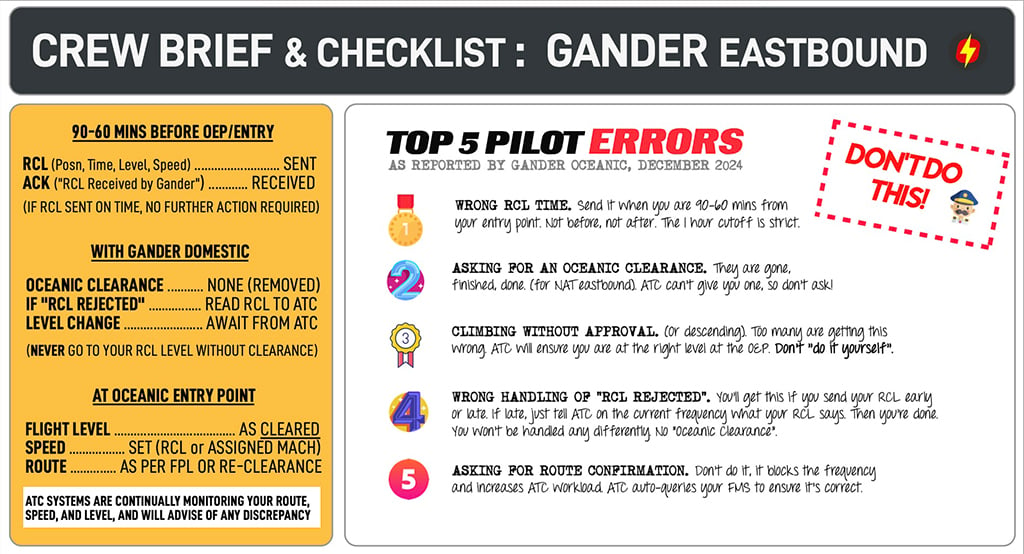

ATC Requires New Clearance Procedure for North Atlantic

Pilots no longer need to request an oceanic clearance from air traffic control to cross North Atlantic airspace, but a new request for clearance (RCL) procedure designed to streamline operations in the heavily trafficked region has sown some confusion in its early implementation.

RCL messages, delivered by voice or Aircraft Communications Addressing and Reporting System (ACARS) data link, specify a flight’s oceanic entry point (OEP), the estimated time of arrival at the OEP, the optimal speed, the requested flight level and the maximum flight level the aircraft can maintain at the OEP.

Developed by the North Atlantic Systems Planning Group, an International Civil Aviation Organization regional planning entity, the RCL procedure aims to take advantage of newer technologies available to air navigation service providers—namely, controller-pilot data link communications for messaging and ADS-B/ADS-C for surveillance, as well as improved computer interfaces between domestic and oceanic air traffic control (ATC) sectors. (See NAT OPS Bulletin 2023_001 Revision 5.)

“The idea is that with all the fancy tools ATC now have at their disposal, we have reached a point where the Oceanic Clearance is no longer required,” explained OpsGroup, a membership organization representing controllers, dispatchers, pilots and schedulers. “It sounds drastic, but think of it this way: The [North Atlantic] will now just be the same as the rest of the world—you fly what is loaded in the FMS [flight management system] or as amended by ATC.”

Pilots are responsible for submitting ACARS RCL messages during prescribed time windows to oceanic control centers that will acknowledge receiving the request, then provide a flight profile to domestic ATC centers—the radar sector before the ocean. Domestic centers guide a flight to the level an oceanic center has assigned.

“Once you submit the RCL, the response we’re going to give you is ‘RCL received by Gander’—that’s all you’re going to get,” explained Robert Fleming, Nav Canada manager of area control center operations for the Gander flight information region.

“It means we have your wish list,” Fleming added. “We’re going to try to develop a profile, and we communicate that profile to Gander domestic, Moncton domestic or Montreal domestic, and they will be responsible to transition you to that profile prior to the oceanic entry point.”

ATC works within a band between the requested altitude and the maximum flight level to assign an altitude at the OEP, Fleming said.

“The RCL level may not be the level that we can accommodate,” he advised. “We get significant clumps of traffic that will hit oceanic entry points at the same time. If I get three aircraft hitting within 1 min. of each other, all requesting 37,000 ft., there’s no way I can make that happen. Just keep in mind, you’re not the only flight up there.”

A Rough Start

The RCL procedure went into effect during 2024 in the Gander, Shanwick, Santa Maria, Bodø and Reykjavik oceanic control areas. It got off to a rough start. “The number of pilot errors following the introduction of the new ‘No Oceanic Clearance’ procedure is turning out to be far higher than expected,” OpsGroup wrote last December, referencing the Gander oceanic control area specifically. “[T]he very high level of non-compliance with this new procedure is surprising and troubling.”

According to Nav Canada, the top five errors pilots have committed are: sending an RCL at the wrong time—Gander requires them 90-to-60 min. prior to reaching the oceanic entry point; asking for an oceanic clearance; climbing or descending without approval; wrong handling of ‘RCL Rejected’ messages; and blocking ATC radio frequencies by asking for route confirmation. Voice affirmation of the route is unnecessary because ATC auto-queries the FMS to ensure it is correct.

During a Jan. 23 webinar hosted by aviation manuals and safety management system provider Nimbl, Nav Canada’s Fleming said controllers had seen an unprecedented number of errors involving RCL submissions.

“We’ve seen more safety events in the last seven weeks in Gander domestic than we’ve had in the last nine years,” Fleming said. “It doesn’t mean anything bad happened, it just means that something out-of-the-norm happened that we had to intervene and mitigate.”

Controllers had flagged 43 lateral errors. “That’s 43 times Gander domestic had to intervene with an aircraft because the routing that was contained within the FMS was not the routing that was issued to that flight,” Fleming said. “These are all route amendment clearances from the flight plan. We uplink the route clearance and for whatever reason, the execution and loading of that route clearance was not done correctly.”

There were three vertical deviations. “Normally, it’s 300-400 ft. before we catch the actual vertical deviation,” Fleming said. “That’s when we’ll stop the flight, ask [pilots] what their intents are and get them back on the cleared altitude that they should be maintaining going into the oceanic entry point.”