This article is published in Aviation Week & Space Technology and is free to read until May 14, 2025. If you want to read more articles from this publication, please click the link to subscribe.

Collins Aerospace has refined its concept for the accessibility of a personal motorized wheelchair.

Unfazed by the new U.S. administration’s stances against sustainability and inclusion, the cabin interior industry is keeping those priorities on its agenda, committing to reducing aviation’s carbon footprint and making air travel more accessible.

Both themes dominated the Passenger Experience Conference (PEC) and Aircraft Interiors Expo (AIX), held in Hamburg, Germany, April 7-10. Exhibitors are still working to make the most of a fuselage’s interior, cut costs and offer more luxurious business-class and first-class seats, but sustainability and inclusion are becoming deeply rooted.

- The in-service fleet is slowly being improved

- Guidelines, research and development activity are bringing new principles

Still, the slow progress is perplexing. Given their faster development cycles, cabin interiors already could be far more sustainable than airframes or engines. Their designers could have adopted a cradle-to-grave approach for the seats, sidewalls, carpets, galleys, lavatories and—with more difficulty—inflight entertainment systems. Smarter material sourcing could make reuse or recycling doable. Over the average 22-year lifetime of an aircraft—a number Airbus disclosed in 2019—a cabin interior is refreshed several times, making greener design even more compelling.

In the absence of regulation, the higher cost would leave the first mover at a competitive disadvantage. However, that increase could be acceptable, if one considers the low sensitivity of air travel demand to higher fuel prices.

Is it worth pursuing greener cabins? Fossil fuel consumption accounts for some 90% of an aircraft’s carbon footprint over a life cycle. But the cabin represents a respectable 10% of the aircraft’s weight. And the tons of plastics that a cabin refurbishment project sends to the landfill make it advisable to think differently.

Sustainability concerns are becoming omnipresent in the cabin interiors industry, and the sector has been creating its own guidelines. Component manufacturers are working toward circularity, be it reuse or recycling. Amid this awareness, ignoring sustainability when creating a new cabin can only be intentional.

As for accessibility, making room onboard for a personal wheelchair or adding grab handles in a lavatory is neither rocket science nor a threat to profitability. Technical advancements are real but come late, and their sluggish adoption raises questions. Disability advocates are asking when carriers will make investments to prove they care about passengers with special needs. The Air4All lobby and PriestmanGoode designers presented a viable, albeit imperfect, proof of concept at AIX in 2022 to board personal wheelchairs, but its service entry remains years away.

To inform customers about their cabin design sustainability options, Airbus has created an eco-efficiency index, starting with seats. This enables the customer to compare seat models, Wolfgang Wohlers, Airbus senior vice president of cabin and cargo programs, said April 8 at AIX. Weight is the predominant factor in the index due to its relevance to fuel burn.

Also in early April, the Green Cabin Alliance (GCA), a consortium of a dozen cabin design and manufacturing companies, released its Good Practice Guide focused on circularity, data transparency and finding a sustainable business model. “In 2021, the alliance was created because of the numerous questions being asked about cabin sustainability, and nothing seemed to be there to support,” Belinda Mason, a color, material and finish designer at UK-based Avic Cabin Systems, said at PEC on April 7.

Is going greener costly? Not always, Mason answered. Avoiding the creation of waste means better planning of material use, which may generates savings.

Airbus’ index and the GCA’s guide may help shape the industry’s future. Cabin refreshes of a widebody airliner consume 75 metric tons of material over the aircraft’s lifetime, IBA Group Manager William McClintock said at PEC. Locations of aircraft refurbishment or dismantling operations where old cabin parts can be collected are well known, Lisa Conway, chief revenue officer of leather recycling specialist Gen Phoenix, said at PEC. Gen Phoenix creates seat covers and other components.

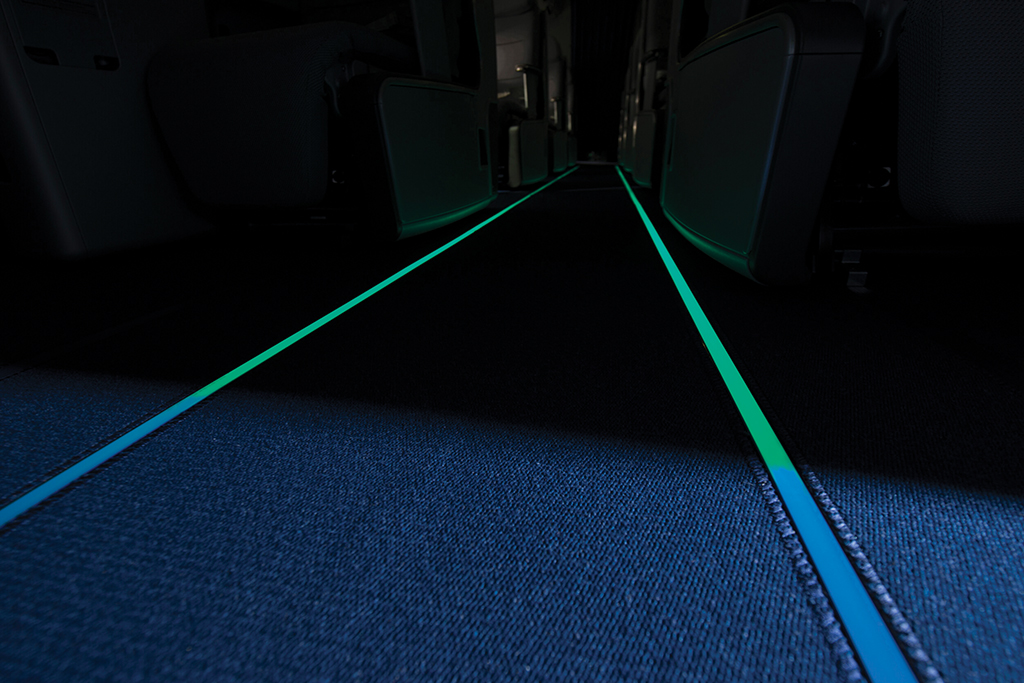

For floor path emergency markings alone, Lufthansa Technik estimates the annual global waste is 10 metric tons, as carriers replace them every 6-7 years. The company is studying the next generation of such markings in which thermoplastic polyurethane supports colored glass tiles. Both color pigments could thus be recovered, while the support would be shredded and melted to create a new one, Lufthansa Technik Product Manager Franziska Voerner said at AIX.

Also addressing the recycling issue, Airbus has changed its material policy for cabins to allow suppliers to include up to 25% of recycled materials instead of providing 100% new components, Wohlers said.

Diehl Aviation has matured its Eco Bin concept for an entirely recyclable overhead baggage compartment, the materials of which can be reused to manufacture other cabin components. Instead of using a variety of materials, which makes it difficult to sort out the recyclable ones, the Eco Bin is made of only polyetherimide thermoplastic composites and metal. Both materials are recyclable, says Carsten Laufs, senior vice president of product innovation and digitalization. The components are bolted together, avoiding the use of glue or adhesives and facilitating the dismantling process.

At the end of the life cycle—up to 20 years—the bin can be recycled and repurposed into other aircraft interior components, such as brackets. The Eco Bin is weight-neutral, meaning lighter components offset the addition of screws. The proof of concept stands at technology readiness level (TRL) 5, meaning it is close to the required maturity (usually TRL 6) to launch product development. If Diehl were to find a launch customer today, the product could enter service in two years, Laufs said.

With one of the most advanced cabin accessibility programs, Collins Aerospace has refined its concept for supporting a personal motorized wheelchair, aiming to meet passenger needs and operator requirements. The demonstrator’s introduction marks progress in enabling people with reduced mobility to fly with dignity. For wheelchair users, air travel involves staff-assisted boardings and entrusting their custom-made, expensive vehicles to baggage handlers. Disability rights organizations have put the issue in the spotlight in recent years.

Taking into account feedback, Collins has ensured carriers do not lose any seating density or revenue or face a longer boarding phase, Cynthia Muklevicz, vice president of customer and business development for interiors, explained at AIX. The Prime wheelchair seating platform relies on minimal handling. The platform is located close to the door, in front of a row of seats. A small workstation for the cabin crew is kept in a folded position.

When the passenger enters, a single member of the ground staff secures the wheelchair to a four-hook restraint system, similar to those on buses. The wheelchair would make one business-class seat or two economy-class seats unavailable. At deplaning, this passenger is the first out and does not have to wait for three ground personnel to help with transfer, Muklevicz said.

Since Collins introduced the first version of the platform last year, engineers have refined the restraint system and tray table, said Shawn Raybell, director of business development. The company is talking to the FAA about the restraint system. Motorized wheelchairs already have a standard for seat belts, Raybell added.

While the platform can be built into a new aircraft, Collins is prioritizing retrofit and foresees service entry within three years.

Thales, meanwhile, is developing new features for the hard of hearing. The seatback screen could transcribe and translate passenger announcements, Thales InFlyt Chief Technology Officer Tudy Bedou said at AIX. Engineers are targeting 90-95% accuracy with a 10-sec. latency. The system uses the original audio channel, making the performance superior to that of a smartphone, which is susceptible to background noise, Bedou says.

For inflight movies, Thales is creating an avatar for sign language translation, which Bedou says provides a better passenger experience than reading subtitles. Thales expects to have the avatar available for safety videos this year, before video on demand is added.

For the visually impaired, Diehl has designed more suitable lighting scenarios in the lavatory. Focusing on contrast and highlighted signs, they help passengers find the faucet and soap dispenser, among other components. The lavatory also incorporates Braille characters and a synthetic voice (“you have found the flush push-button”). Engineers need at least two more years to complete development, Laufs said.

To improve lavatory accessibility, Diehl has studied how people with reduced mobility transfer from their wheelchair. Engineers have added fixed, foldaway grab handles and a removable hanging bar. They have created twinning lavatories, in which the cabin crew folds away the partition wall between the two lavatories, making room for the passenger and the wheelchair. Diehl expects the new product to enter service next year on Asiana’s Airbus A330ceos.