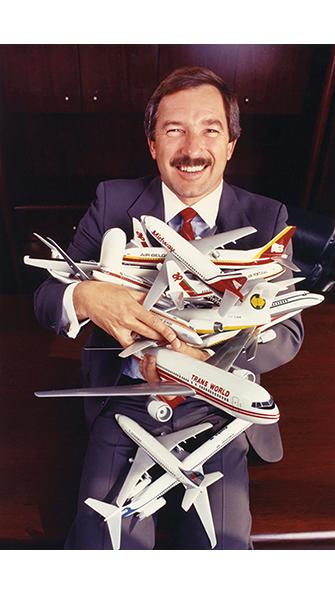

Udvar-Hazy’s life in one picture: aircraft and airlines.

One of the biggest achievements of Steven Udvar-Hazy’s storied career has been a decades-old secret to most in the industry: It was he who leased Ryanair its first few Boeing 737s.

Some may ask why that is a big deal. There are several reasons why. The least spectacular is that he helped create one of the most successful airlines in the world. But to understand the real significance, one has to dig deeply into one of the biggest rivalries in aviation history—between Udvar-Hazy, who invented aircraft leasing in the U.S., and Tony Ryan, who did the same in Ireland with Guinness Peat Aviation (GPA). Ryan also happened to be the co-founder of Ryanair, and there was no way Udvar-Hazy’s International Lease Finance Corp. (ILFC) would ever lease an aircraft to Ryanair.

- Founding of ILFC in 1973 launched the global aircraft leasing industry

- He has had a major influence on commercial airliner design

The episode that unfolded is typical for a man whose life and career has been unusual in so many ways.

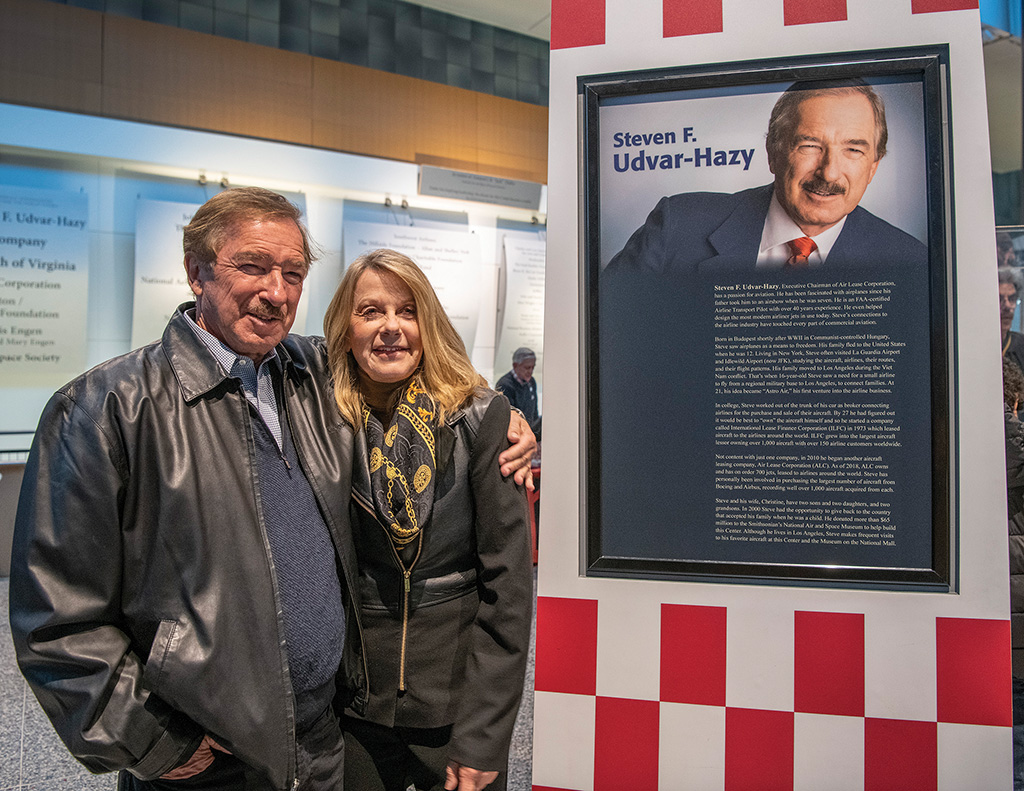

Over the years, Udvar-Hazy has become—and still is—one of the most influential figures in the industry, working with Boeing and Airbus on details of aircraft designs and actually changing them, a businessman who set up two large leasing companies and has helped create or rescue more airlines than one would imagine.

“Steve’s biggest achievement is actually founding the aircraft leasing industry in 1973,” says John Plueger, Air Lease Corp. (ALC) president and CEO and Udvar-Hazy’s closest partner since the late 1980s.

“Many airlines around the world owe their existence to Steve Udvar-Hazy and were pleased that he was around when they needed him to be there,” says Willie Walsh, director general of the International Air Transport Association (IATA).

Even his fierce competitors, most of them based in Ireland, acknowledge the role Udvar-Hazy has played in building their sector. Lessors now own more than half of the world’s commercial fleet either through direct orders or sale-and-leaseback deals in which they buy into airline fleets using their credit profile that is typically more advantageous than that of cash-strapped airlines.

At one point, “Steve [Udvar-Hazy] wanted to buy some [Airbus] A310s, widebodies on speculation,” former Airbus chief salesman John Leahy recalls. “That’s how he opened up the entire leasing market and also opened up an opportunity for lots of airlines to operate new aircraft that would otherwise not have been able to afford them.”

How did he become so successful? It was his seemingly endless “passion for aviation and truly encyclopaedic knowledge of aircraft and airlines,” Plueger says. “He knows city-pairs, he knows distances, and he can equate them to aircraft types.”

That is only part of it, though. An urge for the next big deal, probably inexplicable for many outside the world of dealmaking, seems to drive Udvar-Hazy even now, at age 75. For example, in order to get the new Italian airline ITA Airways to sign ALC leases, Udvar-Hazy took multiple trips from Dallas to Rome on the company’s Gulfstream G650. What’s more, the airline is a startup with a highly questionable business outlook and a pretty high-risk profile that would deter most lessors.

It is also not suprising that someone with this drive would spend a good part of what should have been a family vacation in Hawaii flipping through OAG timetables instead, as Leahy, a business partner and friend, recalls. After having studied the timetables, Udvar-Hazy told Leahy how he would optimize a particular airline’s network and fleet if he were asked. Udvar-Hazy, of course, had many occasions to do so.

New Homes

Udvar-Hazy’s roots are in Hungary. After the brutal Soviet knockdown of the 1956 uprising there, Udvar-Hazy’s father decided it was time to leave. The family somehow made it close to the Austrian border by train, then traveled by horse and carriage, but many snow-covered landmines stood between them and the Austrian border. Two years later, the Udvar-Hazys finally made it to Sweden, finding a temporary residence in Stockholm. His father went to law school, and young Steve, then 11, spent much of his free time watching airplanes at the Stockholm airport. “I was already an airline maniac,” he recalls.

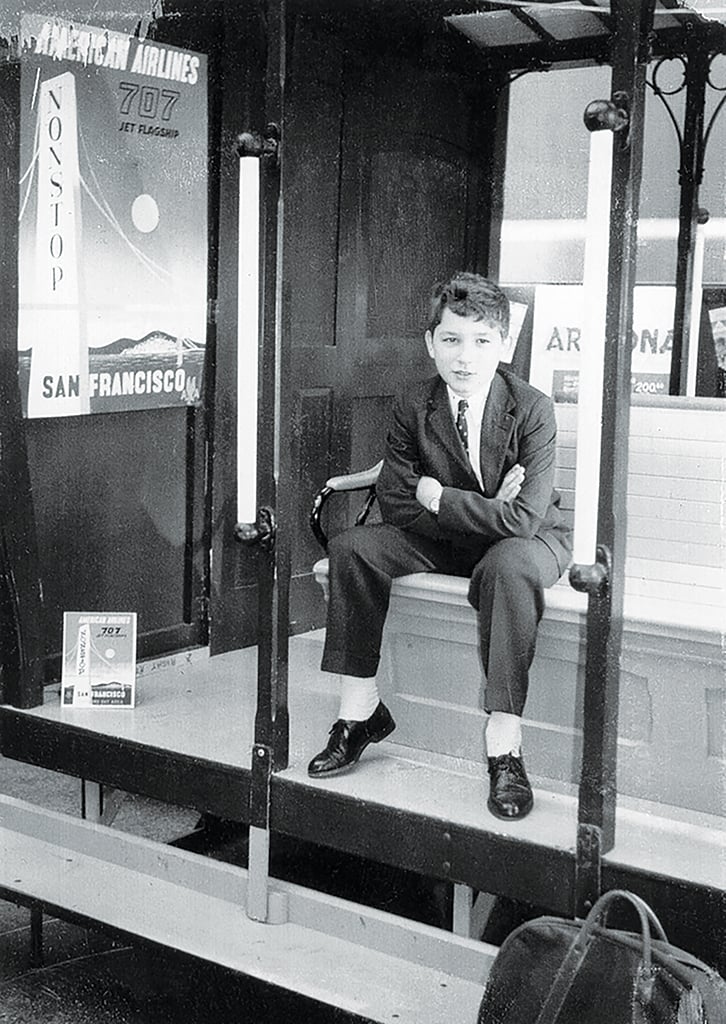

His father managed to obtain a green card and went ahead alone to the U.S. to get established. The family followed a few months later and settled in New York. “I came to America when I was about 12 years old,” Udvar-Hazy says. “The big sports were football, baseball and basketball. We never had baseball or American-style football in Europe in the 1950s, and I was not tall enough to play basketball. Instead of playing those sports in Central Park, I was telling my parents that I was going to the library to study.”

He actually was going somewhere else. There was a subway line out to Queens that ended a short walk from LaGuardia Airport, a place that was much more interesting to him than a library. “There was no security. I would talk my way into hangars,” Udvar-Hazy remembers. “A couple of times, I got up into the control tower. I told them I was doing a school paper on air traffic control so they invited me up.” He saw the Super Constellations, Convair 440s, DC- 6s and DC-3s—Boston-based Northeast Airlines still operated them into LaGuardia. “It was fascinating, and I loved it,” he says.

Udvar-Hazy later included Idlewild, now John F. Kennedy International Airport, into his excursions, where he saw international airline aircraft, too, including those of Lufthansa, Alitalia and many others. “Of course, I had the yearning to fly as a pilot, but mainly I was interested in the business side and what the planes were doing and how they were being operated.”

Steps Into Aviation

Udvar-Hazy may have left Hungary in 1958 as a young boy, but links to the country continued to play a very important role in his life into the 1970s and well after he had founded ILFC. That was in part because he was able to fly his first airplane at age 14. His parents knew some Hungarian immigrants who had a flight school in Ohio that operated a Piper Cub, a Citabria and a Cessna 195. Even though young Steve did not have a license, the friends let him handle the takeoff and fly the aircraft en route, although he was not allowed to land it.

Another Hungarian refugee, Leslie Gonda, is inextricably linked to Udvar-Hazy’s launch of ILFC in 1973. The Gondas had left the country earlier than the Udvar-Hazys, traveling by ship from Spain to Venezuela right after World War II. They eventually moved to Los Angeles, to which the Udvar-Hazys relocated in 1962. The Gondas wanted to send Hungarian forints back to support relatives at home, and the Udvar-Hazys had some savings in the Hungarian currency, so they started a private money exchange to the benefit of both families. Steve and Louis Gonda, Leslie’s 17-

year-old son, became friends and would go to the beach together, “chasing girls and all these other funny things,” Udvar-Hazy recalls.

Steve told Leslie about his passion for aviation and his idea to start a small company to buy aircraft and lease them to airlines. At the time, Udvar-Hazy had made some extraordinary first steps in aviation, but he was nowhere near being able to buy an aircraft. He had $50,000 and needed another $50,000. Leslie Gonda sold a gas station to help fund Steve’s dream: Leslie and Louis became partners with Udvar-Hazy and bought a DC-8 that they leased to AeroMexico. “We never imagined more than three or four planes,” Udvar-Hazy says now. “It was just going to be a hobby.”

Before buying aircraft, Udvar-Hazy had started consulting to airlines on network and fleet issues. One of his first consulting jobs was with Aer Lingus, which flew Carvairs, Fokker F-27s, Vickers Viscount 800s and BAC-111-200s as well as two Boeing 720s and a few 707s. “I thought: What a stupid airline that has 30 aircraft and seven different types,” Udvar-Hazy says. Aer Lingus paid him a $5,000 fee and sent a ticket to Dublin so he could work out a five-year fleet plan. As he recalls, the plan was simple: “Replace all this junk flying around intra-European with 737-200s intra-European.” Another problem Aer Lingus had was seasonality: In the summer, it had too few aircraft and in the winter too many. Udvar-Hazy found other operators to fly the Aer Lingus aircraft during the winter season.

In 1968, he started brokering aircraft. Air New Zealand was trying to find a buyer for a Lockheed Electra. Udvar-Hazy was 22 years old and still in college, but he found a buyer for the aircraft in Alaska—the airline bought the aircraft for $1 million, and the young broker got a $50,000 commission.

Why would Air New Zealand task a 22-year-old college kid out of Los Angeles with a deal like this? “They did not know how old I was because at that time we used telegrams,” Udvar-Hazy says. “They had no idea.” Of course, that changed when he landed in New Zealand for the first time and met his counterparts. “They were a little bit surprised,” he recalls. “But I had studied everything I could find about Air New Zealand, its history and operations. I tried to be knowledgeable.”

This anecdote highlights two other elements of the Udvar-Hazy story: incredible audacity even at a young age and the ability to forge long-term relationships. Fifty years after that 1968 deal, Udvar-Hazy is still doing business with Air New Zealand. He has made numerous additional transactions with Aer Lingus, as well.

IATA’s Walsh had just taken over as Aer Lingus CEO when Udvar-Hazy helped save the carrier from bankruptcy in 2001. Udvar-Hazy flew in one day from Los Angeles in his private jet and agreed to a sale-and-leaseback deal for some Boeing 737-500s that gave the airline access to much-needed cash, Walsh recalls. Aer Lingus survived, became part of International Airlines Group (IAG) and has long been a success story.

Before Udvar-Hazy flew back across the Atlantic, he told Walsh that “he hoped [he] would remember the deal,” the former Aer Lingus CEO says. “And, boy, has he reminded me of it ever since.”

Enter John Plueger

Although Louis Gonda was a friend in Udvar-Hazy’s early college years, he was not the kind of partner that Udvar-Hazy wanted at ILFC. The Gondas were still shareholders, and Louis was working in finance, but his interests were more in the legal or real estate realms than aviation. Louis and Leslie left the business finally when they and Udvar-Hazy sold ILFC to American International Group (AIG) in 1990.

John Plueger, a certified public accountant who had joined ILFC as a controller in the finance department in 1986, became the partner for whom Udvar-Hazy was looking. Plueger shared Udvar-Hazy’s passion for flying—Udvar-Hazy had earned his private pilot’s license almost at the same time as his driver’s license—and Plueger was flying small aircraft for a charity carrying sick children on weekends, which is where he met Alan Lund, who became ILFC’s chief financial officer in the 1980s.

These were good preconditions for a partnership between Plueger and Udvar-Hazy, but what really did the trick was a trip Plueger took to Indonesia. Garuda Indonesia was interested in replacing its fleet of aging McDonnell Douglas DC-9-30s, but no one at ILFC was available to go meet with the airline—except Plueger. He took the four-stop DC-10 flight from Los Angeles via Honolulu, Biak and Bali to Jakarta and came home with a big deal for eight leased 737-300s. “John quickly became intoxicated with the business side of airlines,” Udvar-Hazy says.

The two have worked together ever since, except for a brief time when Udvar-Hazy left ILFC and Plueger stayed on for a while as the CEO. Udvar-Hazy says AIG President and CEO Robert Benmosche had promised to sell 25 aircraft from the ILFC portfolio to him for $1 billion to raise cash to repay the U.S. government for bailing it out. Udvar-Hazy wanted to use the 25 aircraft as the foundation for a new leasing company. But then Benmosche “reneged on the deal, and I was very upset,” Udvar-Hazy says.

Udvar-Hazy did not have a noncompete clause in his departure deal, and so he decided to set up another leasing company, ALC, in 2010. “I retired for 5 min.,” he says. “I was still young and thought, ‘Why don’t we set up another small leasing company?’” He raised $1.2 billion in equity from banks such as JP Morgan and Credit Suisse, and a year later, ALC raised another $1 billion on the New York Stock Exchange.

Without planning it, Udvar-Hazy had picked a good time to start another leasing venture. The industry had begun to climb out of the global financial crisis, and demand was coming back. Interest rates were low, fuel was cheap—airlines needed aircraft quickly, and many could not afford to finance them. But some could: ALC’s first aircraft was an Airbus A320 leased to Air Berlin.

“I have about a 90% success rate,” Udvar-Hazy says. Air Berlin, which stopped flying in 2017, is part of the 10%. Another bigger part is Varig, the former Brazilian airline. “That’s the airline that I lost the most amount of money on,” he recalls. “We had a long relationship with them on widebody aircraft, including the DC-10-30s, 747-300s and -400s.” Varig went out of business in 2006.

Varig, Air Berlin, Alitalia, ITA, Aer Lingus—Udvar-Hazy has not been averse to entering risky deals at times. But those bets that paid off did so with generally higher margins than those deals with well-established, well-funded carriers with access to other sources of funding. In the U.S., he was involved in the creation of America West Airlines and JetBlue Airways, among others.

At ALC, Udvar-Hazy brought the band back together. Plueger had succeeded him as CEO at ILFC but eventually he stepped down, too. The new lessor was also an opportunity for the two partners to work together again. Udvar-Hazy is now executive chairman and Plueger the CEO. Both visit customers frequenty, but Plueger deals more than Udvar-Hazy with ALC as a business. What they have most in common is their love of flying.

Udvar-Hazy had at some point ordered two G650s privately, which were later transitioned to ALC to be used as company aircraft. The company employs pilots, but whenever they can, Udvar-Hazy and Plueger, both air transport-rated pilots, fly themselves. They often flew together—until the board of directors made clear that it was better for them to fly with a different colleague instead.

Both Udvar-Hazy and Plueger argue that their time in the cockpit has helped them understand the daily operational challenges of airlines. Being forced into detours flying into Europe because of air traffic control constraints raised their awareness of what their customers go through all the time.

Aircraft Design

Udvar-Hazy’s detailed knowledge of aircraft design is also something that Airbus and Boeing have gotten to know—and sometimes hate. Without Udvar-Hazy, Airbus likely would not have built the A350 in its current form.

“I had a lot of meetings with the [Airbus] leadership team,” Udvar-Hazy recalls. “They came up with the idea of a kind of low-cost derivative solution as competition to the [Boeing] 787. They thought they could do it for €2-2.5 billion [$2-2.5 billion]. But the aircraft did not really have a better wing; the 787 was faster. It had other characteristics that were more like a super A330.”

During the meeting, however, Udvar-Hazy “went through a lot of different designs with a different wing sweep,” he says. “I also thought they [would] have to make the fuselage just a little wider than the 787 and learn a lot from the 777. I gave them like 20 points, including actual detailed schematics.”

Airbus continued to balk until Udvar-Hazy went on stage at an International Society of Transport Aircraft Trading Americas conference and said: “If Airbus does this first version of the A350, they would only get the silver medal, and Boeing would get gold.” That finally changed the thinking in Toulouse, and Airbus started work on the A350 that the industry knows today.

ALC has not only ordered the A350, it is also the largest lease customer of the A330neo, which looks remarkably similar to that first A350 design that Udvar-Hazy rejected back in the mid-2000s.

On the Boeing side, Udvar-Hazy has been among the harshest critics of the 737 MAX saga and the shortcomings of that aircraft family. ALC is also one of the largest buyers of A321XLRs, the long-haul version of the A321neo that is slated to enter service in the first half of 2024.

But the most unlikely deal still is that Ryanair 737-200 order. “They needed jets to fly from Stansted to Dublin but would not do business with me because I was the enemy,” Udvar-Hazy says. So he created a paper company in Bermuda called Atlantic Aviation Holdings that was owned by ILFC, a detail that escaped Tony Ryan. Ryanair leased the aircraft, and Ryan never discovered the identity of the lessor behind the lessor.

Michael O’Leary, Ryanair’s long-time CEO, has known the secret for some years and recognizes the humor in it. O’Leary sent Udvar-Hazy a signed €20 bill addressed to “the poor Hungarian farmer that helped start Ryanair.”

Comments