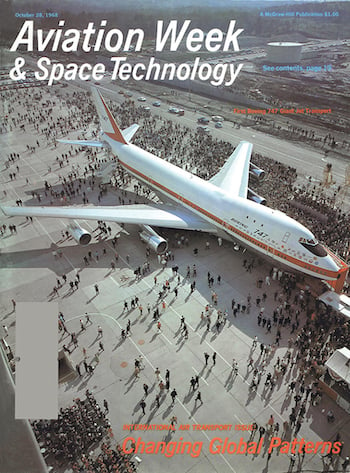

More than 54 years, 1,574 aircraft and 17 major derivatives separate the first 747 rollout in September 1968 and the final one in December 2022 (pictured).

In February of 1966, almost exactly 56 years ago, Aviation Week picked up the first news of Boeing’s game-changing decision to design the 747 with a single main deck, which created the blueprint for the world’s first widebody.

That audacious move, revealed just a month before Boeing’s board gambled the net worth of the company to launch the huge new airliner, was emblematic of the company’s bold design approach and signaled the introduction of a slew of innovations that still resonate throughout the industry.

- It embodied a twin-aisle design leap

- The aircraft’s systems redundancy was a hallmark

As the final 747 is delivered, Aviation Week highlights how some of these features—ranging from systems redundancy and sophisticated avionics to simulation and propulsion—reshaped the commercial aviation business for the next five decades.

Credit: AW&ST Archive

But first some context. The widebody design was born of necessity during the 1960s, in an era when everything seemed possible—including what was then seen as an inevitable move to the large-scale use of supersonic transports (SST). The late Joe Sutter, the program’s first chief engineer, who was affectionately known as “the father of the 747,” recalled in 1996: “Many of the airlines, and the people here at Boeing, thought the 747 was an airplane with a limited future because the SST was going to take all the business.”

But the SST, ironically, turned out to be the best thing that could happen to the subsonic 747. “I think that program did a lot of good for the 747, although at the time it wasn’t obvious,” recalled Sutter. Convinced that the Mach 2.5, 250-seat Boeing 2707 soon would dominate the long-haul passenger market, Sutter’s design team expected the 747’s long term future would—at best—be anchored to the needs of the cargo market.

This had not been envisaged in early 1965, when then-Pan American Chairman Juan Trippe warned then-Boeing Chairman Bill Allen that he was considering ordering the recently launched Douglas “Super Sixty” stretched DC-8 unless the Seattle manufacturer planned to study a larger aircraft. Unable to stretch the 707 sufficiently because of its shorter main landing gear, Boeing initially studied full-length double-deck arrangements that stacked one 193-in.-dia. fuselage on top of another.

But even this was not enough to meet Pan Am’s 350-plus passenger load requirement, which was more than 2.5 times the capacity of the airline’s standard 120-seat 707 configuration at the time. As a result, the double-deck concepts were enlarged, and the upper deck ended up with a 197-in.-dia. cross-section that was uncannily identical to the dimensions that would emerge 15 years later in the design of the medium widebody 767. The lower section was extended to 209 in. wide in cross-section.

But Sutter was not a big fan of the double-decker and called it “clumsy.” The design was problematic from a servicing, evacuation and loading perspective. “You ended up with a big wing on a short, stubby airplane,” he recalled.

“Joe Sutter said that was just a dumb idea and it wasn’t going to work,” says Boeing Chief Historian Michael Lombardi. “There was no way to get passengers off the upper deck in an emergency, and he proved that to Juan Trippe and the rest of the team by taking them up into the mockup and having them stand and look down at the floor. They agreed he was right. Passengers would not want to jump out of the cabin [and] go down a slide from that height. That was one of those great moments that leads to discovery.”

Leaning on design work and technology developed for the U.S. Air Force’s CX-HLS strategic airlifter contest—which Boeing lost to Lockheed’s C-5A in August 1965—Sutter’s design team quietly recrafted several 747 concepts around a revised single deck. Designed to accommodate two 8 X 8-ft. seagoing containers side by side, the passenger variant was sized for up to 10-abreast economy-class seating, a radical departure from anything previously considered.

“Right near the contract signing, we conceived this wide single deck,” Sutter said. “Of all the decisions we made, the most important was selecting the single deck. It gave us an airplane that was efficient and extremely flexible and was one of the main reasons for its success.” To enable the floor to be accessed for loading directly through an upward-hinging nose door as on a freighter, the flight deck also was raised up and out of the way to produce the 747’s hallmark upper-deck “hump.”

John Borger—Pan Am’s vice president and chief engineer, who exerted a huge influence on the final 747 concept—had misgivings that the CX-HLS background was making the new design too big and overly biased toward its cargo role. But the single main deck also drove key design decisions, which allayed his earlier concerns about wing placement and emergency evacuation and, just as important, achieved a configuration that could meet Pan Am’s goal of a 30% reduction in transoceanic operating costs. All the design issues were resolved by April 1966, when Pan Am launched the widebody era with an order for 25 747-100s, each costing $20 million.

In hindsight, Boeing’s $1 billion gamble paid off handsomely over the years. Even 30 years ago, as Boeing marked the delivery of the 1,000th 747—a 747-400 for Singapore Airlines—it noted that, adjusted for inflation, it had sold $148.1 billion worth of 747s since the initial delivery to Pan Am. The subsequent launch in 2005 of the reengined and stretched 747-8 added 155 more orders to the tally, taking production of the overall program to 1,574 aircraft and extending the manufacturing life of the model by more than a decade.

But the impact of the 747 went beyond just Boeing and its suppliers. The aircraft lowered seat-mile costs to new levels, opening up air travel to the masses and establishing the basis of the international transport infrastructure of today. Describing the project as “audacious,” Lombardi says the 747 was very much a product of its time.

“Boeing had this attitude that we can do whatever we need to do, [that] the only limit we have is our imagination. Which was kind of typical of that time—we were building the SST—we were going to the Moon,” Lombardi says. “So, in engineering terms, there was nothing they thought couldn’t be figured out. At the company, engineers had a saying: ‘We will have the really difficult things done by tomorrow, but the impossible will take us a bit longer.’ That attitude typified Boeing and of course Bill Allen, who really nurtured it and defined it in the sense of leadership and risk-taking.”

Widebody Versatility

With the launch of the 747, the widebody floodgates opened, and within 3.5 years of the aircraft’s first flight in February 1969, the new twin-aisle McDonnell Douglas DC-10, Lockheed L-1011 and Airbus A300B had been developed. While none of these other first-generation widebodies boasted the 256-in. external diameter of the 747, the DC-10’s 237-in.-wide fuselage continued in production with the MD-11 derivative through 2001, while production of the 234-in.-wide L-1011 ceased in 1984. In the Soviet Union, Ilyushin began tests in 1976 of the IL-86—forerunner of the IL-96—with a 238-in.-dia. fuselage.

Credit: AW&ST Archive

Aside from the 747, which eventually was developed into a family with three different lengths and 17 major derivatives, only Airbus has come close to maximizing the versatility of the same baseline cross-section. Other than the exceptions of the A380, launched in 2000, and the revised A350 design in 2016, the European manufacturer has stuck with the original 222-in. cross-section of the A300 for all its widebody designs over the past five decades. From the original A300/A310 and subsequent A330-200/300 and A340-200/300, -500 and -600 derivatives, Airbus continues to use the original cross-section for the A330-800/900 versions.

Credit: AW&ST Archive

Safety and Redundancy

The leap in size meant “safety was the biggest single issue” when it came to designing the 747, Joe Sutter recalled. “There was so much to consider because of the sheer change in gauge. We did everything we could to make an airplane people would be confident in. Inside the airplane, a lot of things were designed to give it the ability to survive incidents,” he said.

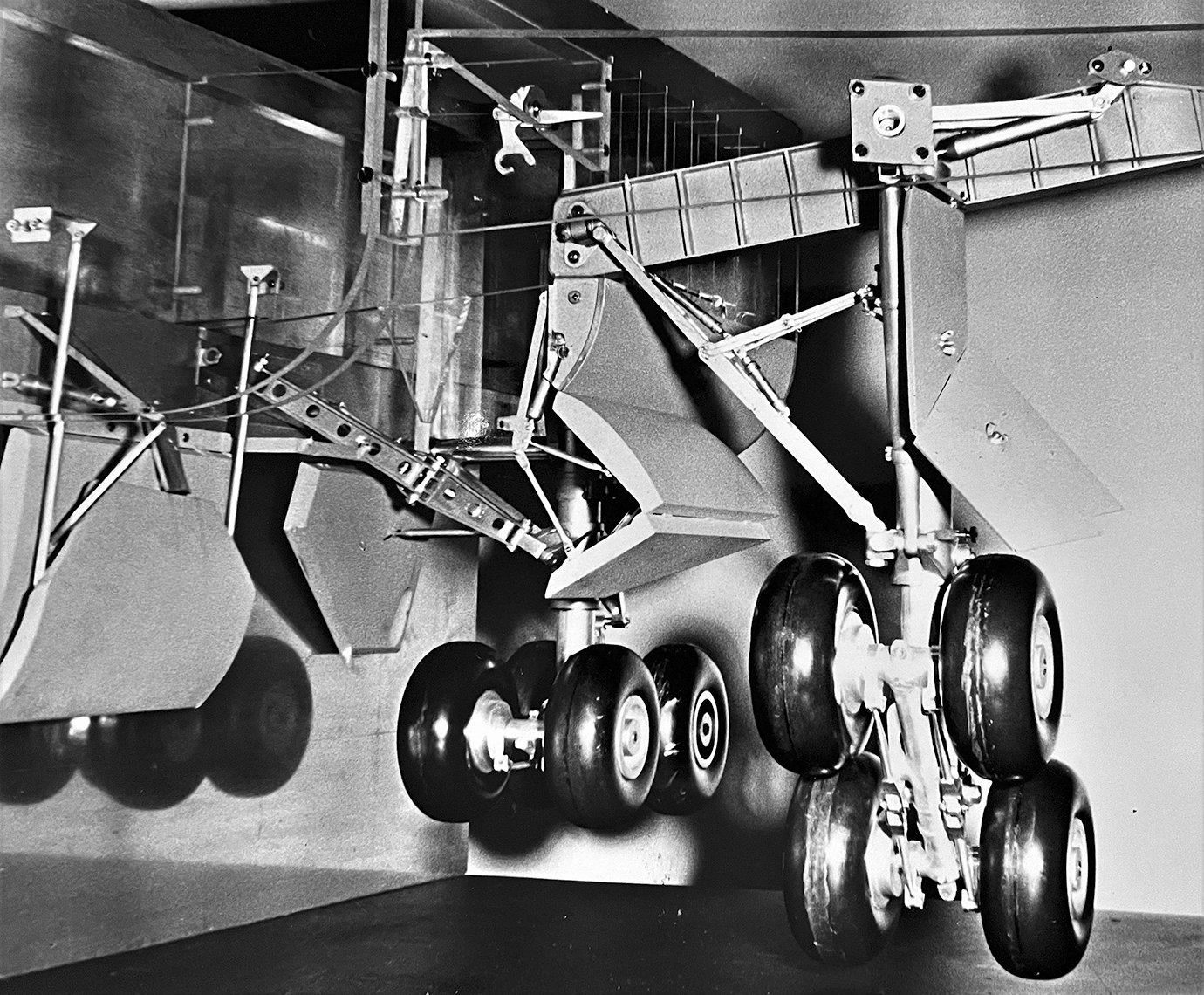

The aircraft was configured with split control surfaces, inboard and outboard ailerons, split spoilers, split elevators and split rudders. “All these systems were powered by four hydraulic systems—an innovation at the time. We even gave it a four-leg main landing gear so that if something happened to part of the gear, the pilot could still bring the aircraft home successfully,” Sutter said.

Credit: AW&ST Archive

The hydraulic systems were completely independent and each driven by a separate engine, while every moving control surface was powered by two systems. Aircraft control around each of the three attitude axes (roll, pitch and yaw) was powered by all four hydraulic systems. The design ensured that the 747 would remain controllable even if two engines failed on takeoff, if any three hydraulic systems failed or if an engine or part of a wing, fin or stabilizer tip was lost through collision. Control actuators were signaled by duplicated cables, and all the electrical circuitry was duplicated as well.

Structurally, the design was a scale-up of the fail-safe philosophy adopted on the 707. However, for extra redundancy Boeing added a third spar to the wing that ran out as far as the outboard engine position mounted 71% along the span. “On an aircraft the size of the 747, putting a third spar in did not put much extra weight in the airplane,” Sutter pointed out. Similarly, the horizontal tail and vertical fin were designed with an auxiliary spar in addition to the front and rear spars. The structure was designed for a 60,000-hr. fatigue life, more than double previous designs.

Credit: AW&ST Archive

Structural suppliers also developed innovations for the program. Northrop, which was responsible for much of the fuselage panel production, designed a special deformable plastic wheel process to form some of the different-shaped stringers—of which there were around 3 mi. in each fuselage. Polyurethane tools also were perfected for crimp-forming heavy-gauge materials, and fiber-laminated stretch lightweight dies were developed for making the enormous skin panels.

Avionics Advances

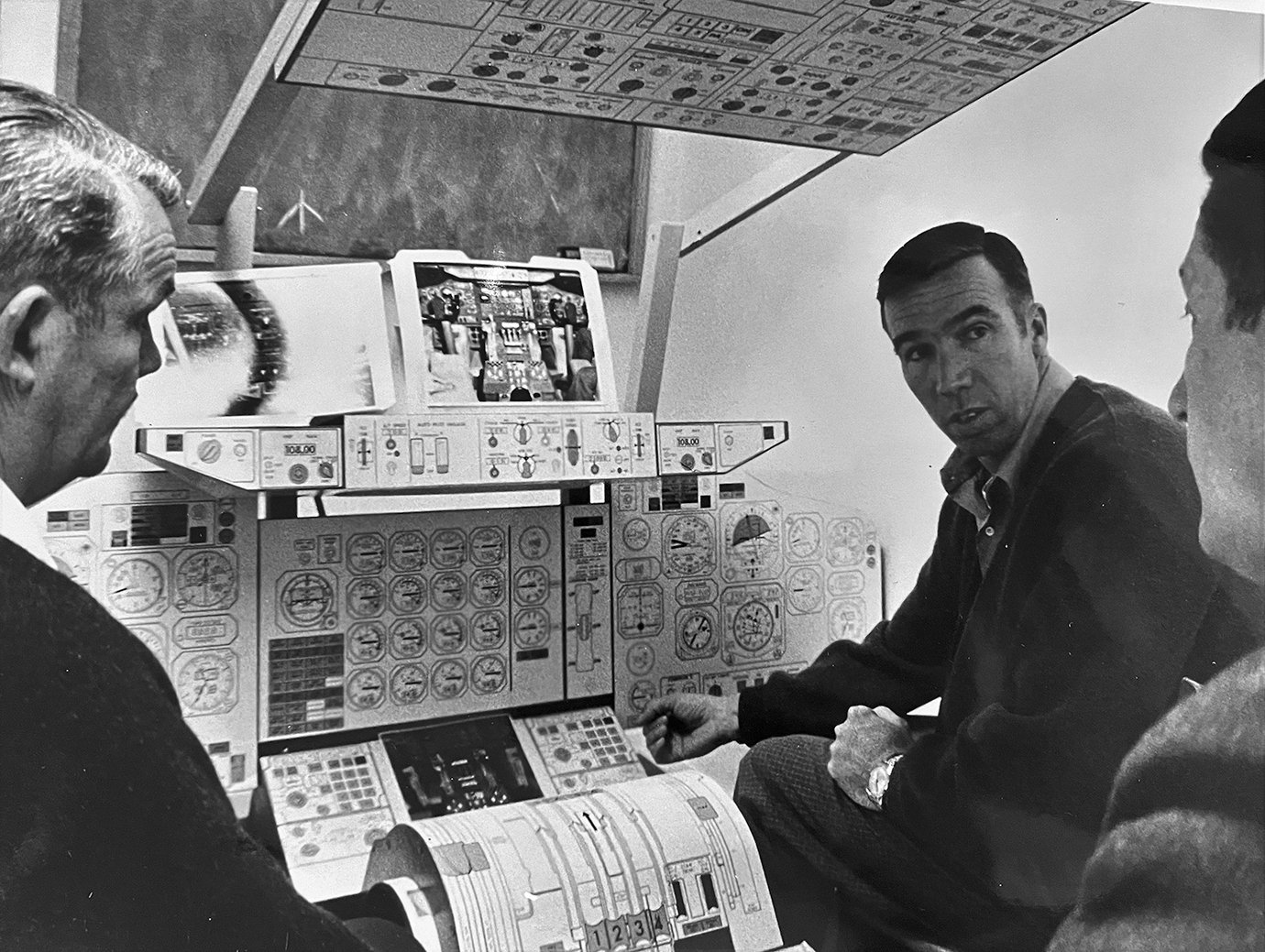

The 747 was the first commercial airliner to be designed from the start with an inertial navigation system (INS) as part of the baseline avionics. In today’s era of satellite-based navigation it is difficult to overstate how much of an advance the INS was at the time for long-range navigation as well as for attitude control. Originally developed by the Charles Stark Draper Laboratory at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology for the Apollo space program and missile guidance, the units were built for Boeing by the Milwaukee-based AC Electronics Division of General Motors.

The main components of the 747 system, known as the Carousel IV (C-IV) navigator, included a digital computer and power supply and an inner turret containing two vertical gyros and two accelerometers, which rotated continuously to offset gyro drift rates. Three C-IVs were on each aircraft, and their accuracy meant that specialist navigators were no longer required for long-range overseas flights.

Another key component of the C-IV was the control and display unit, which could indicate a digital readout of the aircraft’s precise latitude and longitude and the distance and direction to the destination. The novel layout, now so familiar, included a push-button keyboard that enabled pilots to program in up to eight navigational waypoints en route.

Another flight deck innovation was the consolidated automatic flight control system, which combined the auto-pilot and flight director along with a dual-channel yaw damper and autothrottle. The change simplified switching from automatic to manual control and allowed the use of the now-familiar single-mode control panel close to the pilot’s eye level.

Propulsion

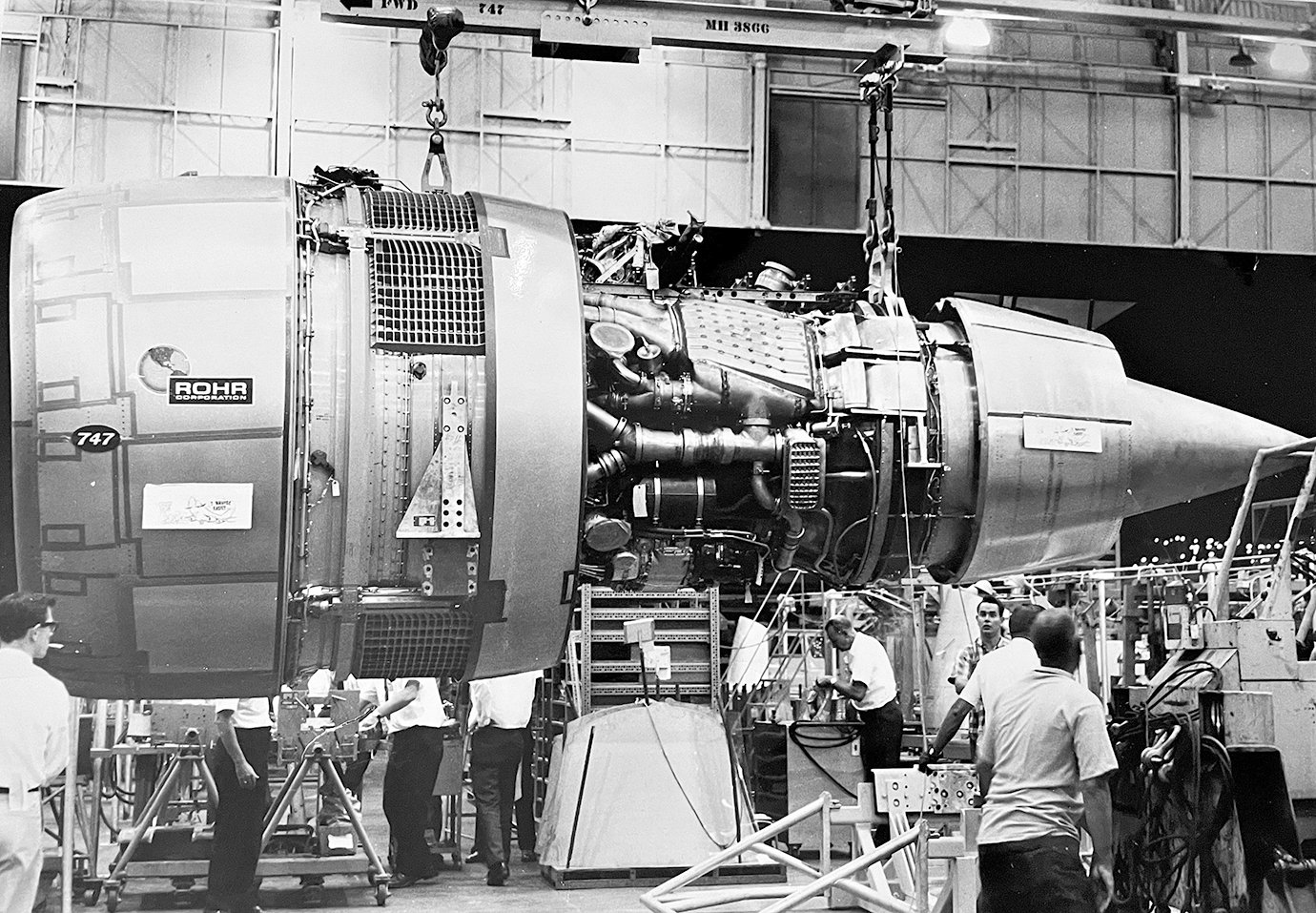

The single most important technological advance on the 747 was the use of the first high-bypass-ratio civil turbofan, Pratt & Whitney’s JT9D. Although originally developed for the CX-HLS military transport contest, in which it lost out to General Electric’s TF39, the JT9D’s selection for the 747 jump-started the development of a new generation of high-thrust, efficient civil turbofans. While the JT9D enjoyed a seven-year monopoly on the 747, the engine’s lead spurred development of the competing GE CF6 and Rolls-Royce RB211 turbofans. They went on to power the other emerging widebody families before eventually being offered on the 747.

Unlike today’s commercial airliner programs, in which engine development generally precedes that of the airframe by a significant margin, the JT9D high-bypass-ratio engine was developed virtually in parallel with the 747 and thus inevitably suffered reliability problems before and after entry into service.

Credit: AW&ST Archive

The challenge was exacerbated by the 747’s rapid weight growth, which forced a faster-than-expected increase in thrust requirement. Beginning with a rating of 41,000 lb., the JT9D was pushed quickly to 43,500 lb. and then 45,000 lb., a trajectory that resulted in turbine temperature problems. During the flight-test program, 55 engines were changed, compared with just one on the JT8D-powered 737 test program.

The progressive improvements in big turbofans in the decades since the birth of the 747 illustrate not only the dramatic advances in thrust and efficiency achieved by the engine-makers but also the adaptability of the 747’s design architecture to accommodate them.

From the 93.6-in.-dia. fan of the initial 43,500-lb.-thrust JT9D used on the earliest variants, engine size and power increased to the 94-in.-dia. fan and 62,000-lb. thrust of the later Pratt & Whitney PW4000 series. Similarly, Rolls’ RB211 family on the 747 grew from 50,000 lb. of thrust on the original 747-200 to more than 60,000 lb. for the final -524 versions developed for the 747-400.

The biggest growth, however, has been demonstrated by GE. The first production 747 with GE engines, an E-4 airborne command post for the U.S. Air Force, was delivered in 1974. The first commercial version, a 747-200B Combi with an 86-in.-dia. fan and 52,500-lb.-thrust CF6-50Es, was handed over to KLM Royal Dutch Airlines in October 1975. The final 747-8, which is to be delivered to Atlas Air on Jan. 31, is powered by GEnx-2Bs with a 104.7-in.-dia. fan and, despite its higher thrust rating of up to 66,500 lb., is about 20% more efficient than some of the engine models used on the 747-400.

Simulation and Training

A new emphasis on advanced training and simulation emerged with the 747—a reflection in part of the aircraft’s greater size and sophistication—as well as an increased focus on safety. A new level of flight simulator was developed for the program that included motion in six axes, beyond the basic roll, pitch and yaw of earlier devices. Now including vertical, lateral and fore-and-aft motion, the new standard simulators for the 747 were made by Conductron, a unit of McDonnell Douglas, and Singer-General Precision’s Link Flight Simulation division, now part of CAE.

Credit: AW&ST Archive

Credit: AW&ST Archive

At the same time, Boeing worked with the best training experts from its future operator group under the Air Transport Association Training Committee to develop the 747 pilot training program through all phases, from ground school to flight training. The collected data was based on specific behavioral objectives and produced a program focused on end-of-training competencies. The resulting “need-to-know” training concept created a blueprint for the advanced pilot training syllabi in use today.

Comments

Thank you Guy and Aviation Week!

Alan Mulally

one imagined the end of the four-engined airliner.