This article is published in Aviation Week & Space Technology and is free to read until Mar 15, 2025. If you want to read more articles from this publication, please click the link to subscribe.

Apollo 17 Cmdr. Gene Cernan was covered in lunar dust after his second moonwalk.

When Harrison Schmitt took off his helmet, he whiffed the same scent all other Apollo astronauts who walked on the Moon have smelled.

“All of the astronauts agreed it smelled like gunpowder,” Schmitt, the Apollo 17 Lunar Module pilot, tells Aviation Week. “You know, we all had, at one time or another, been hunters.”

- Frozen water mixed into regolith could sustain a space-based economy

- Health hazards of powdery lunar soil are an open question

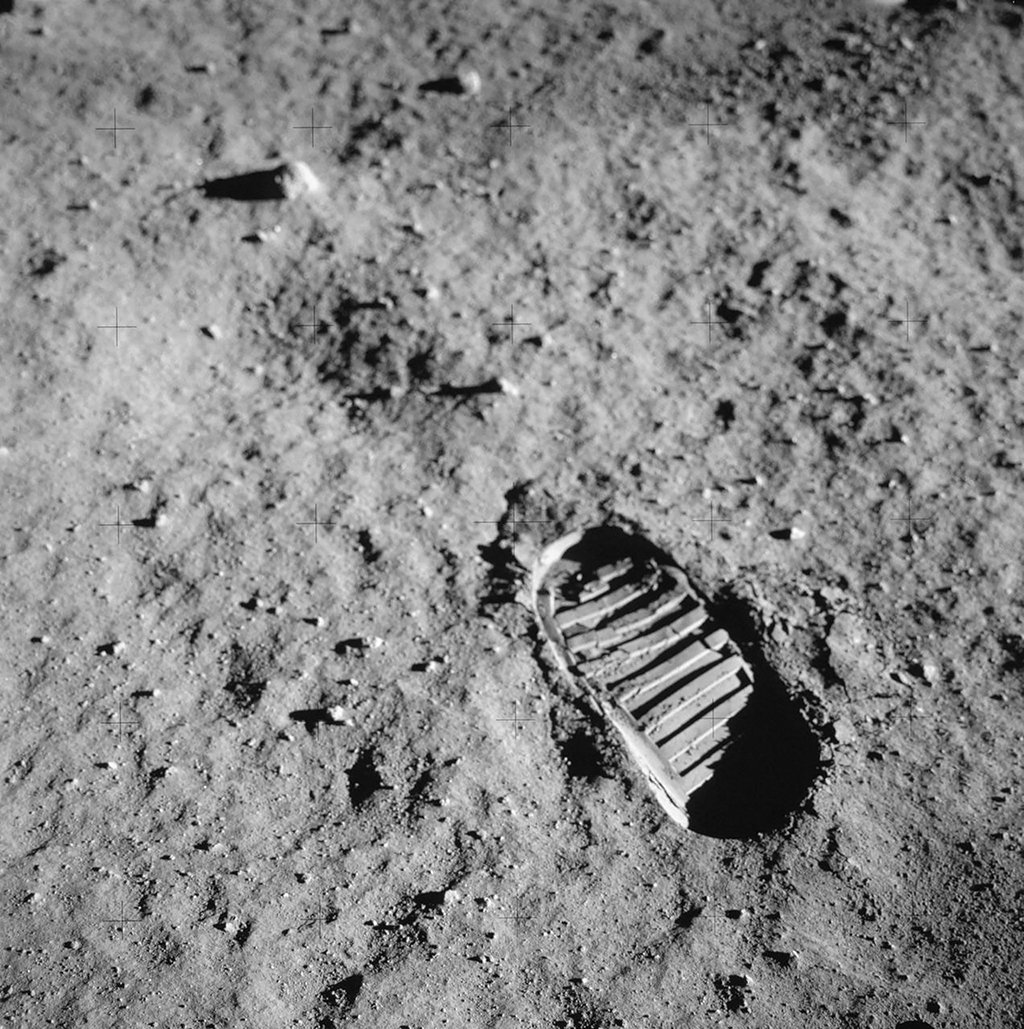

What Schmitt and the other moonwalkers had smelled was lunar regolith: moondust. A gray, fluffy powder, regolith at the microscopic scale is jagged and clings to everything, sticking even to itself in ways not typical of its cousin on Earth.

Apollo 17 Cmdr. Gene Cernan saw lunar regolith as a major barrier. “I think dust is probably one of our greatest inhibitors to a nominal operation on the Moon,” he said in an Apollo 17 technical debrief. “I think we can overcome other physiological or physical or mechanical problems except dust.”

As NASA plans to establish a permanent Moon base via its Artemis program, it is looking to avoid the dangers of lunar regolith, particularly its dusty form, health hazards, proneness to being kicked up by rocket motor thrust and damaging nearby equipment and fine grittiness that wears down tools, seals, joints and other equipment.

But the space agency and lunar wildcatters do not just want to mitigate lunar regolith—they want to exploit it. They see vast potential in the regolith as an ore that, once processed, could fuel and sustain a space-based economy. To balance these opposing concerns, scientists are dreaming up a complex lunar infrastructure, including rocket blast berms, antiregolith spacesuits and laser power-beaming.

For his part, Schmitt, a trained geologist who has studied the composition of the Moon extensively, says the hazards of lunar regolith can be dealt with. “I think we’re much more knowledgeable about its character, and as a consequence probably are in a good position to protect not only humans but machines from its adverse effects,” he says.

Schmitt, also the last living member of the Apollo 17 crew, has talked for decades about mining lunar regolith for helium-3, a rare isotope with uses in emerging technologies such as quantum computing and nuclear fusion. In 2020, he co-founded Moon mining startup Interlune with Rob Meyerson, a former president of Blue Origin (AW&ST March 25-April 7, p. 46).

Others envision mining ice on the Moon, pulling hydrogen and oxygen from frozen water granules mixed into the sandy regolith. Lunar ice is not likely to be found in ice sheets, as billions of years of constant bombardment by micrometeoroids have churned the lunar soil, a process scientists call “lunar gardening.”

If lunar colonists can find a way to excavate frozen H2O molecules from moondust, melt them and crack them into hydrogen and oxygen, the elements could be used as rocket propellant, powering spacecraft ferrying people and space-manufactured goods to and from Earth and into deep space, including Mars. Oxygen and water also provide the basic elements for long-term human survival on the Moon.

Lockheed Martin in a white paper released last year notes that spacecraft mass mostly comes from propellants and that launch is the highest unavoidable cost for a space economy. “Eventually, performing that refueling using propellants already outside Earth’s gravity well, produced from lunar water, avoids the Earth launch costs of delivering that propellant altogether,” the prime manufacturer says in the paper, which envisions a lunar economy in the 2040s.

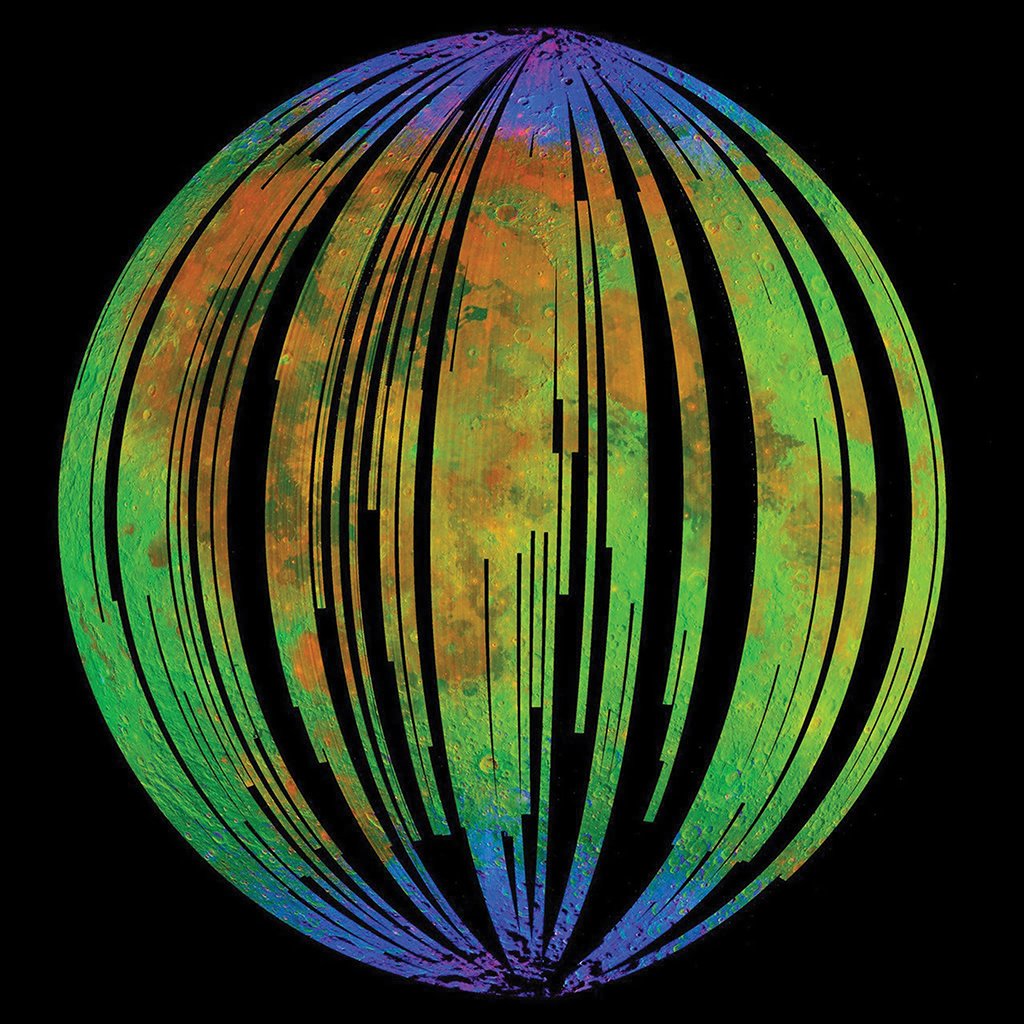

NASA has steadily been accumulating evidence of water on the Moon, but much of its prospecting is inferred from remote sensors. In 2020, the space agency revealed that data from the Stratospheric Observatory for Infrared Astronomy—a Boeing 747SP aircraft modified to carry a 2.7-m (8.9-ft.) reflecting telescope—confirmed concentrations of water in the Clavius crater roughly equivalent to a 12-oz. water bottle per cubic meter of soil.

To get a close look at lunar water, NASA plans to launch Intuitive Machines’ IM-2 lander to the lunar south pole as soon as this month. As part of the Commercial Lunar Payload Services (CLPS) program, the IM-2 lander is to carry the Polar Resources Ice Mining Experiment-1: a drill to extract regolith 3 ft. below the surface and a mass spectrometer to look for water.

“We don’t have great data yet on the distribution of water ice on the Moon,” Kate Watts, Lockheed Martin’s vice president of mission strategy and advanced capabilities for human and scientific exploration, said at the American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics (AIAA) Ascend conference in July. “But what we do have suggests there is plenty—think over 1.3 trillion lb.”

In October, NASA identified nine potential landing regions near the lunar south pole for its Artemis III mission, scheduled to be the first crewed landing on the Moon for the program in 2026. Sites were chosen partly because the locations were close enough to enable astronauts to walk to permanently shadowed regions, thought to contain significant amounts of ice, to gather regolith samples.

The lunar south pole features many permanently shadowed craters with steep walls and deep floors, such as the Shackleton crater, the interiors of which stay permanently dark. Sunlight never touches the floors of these depressions at the poles because the Moon’s small axial tilt of 1.5 deg. means rays come in at very low angles.

Extracting water from shadowy craters could be tricky. The temperature in the cold, dark pits is thought to be about -370F, low enough to trap water molecules from icy comets and to be tough on electronics and batteries. Even charging lunar rovers with a power cable could be problematic.

“We don’t want to be dragging hot cables around in the [permanently shadowed regions],” Rob Chambers, Lockheed Martin’s director of strategy, human and scientific space exploration, said at the Ascend conference. “What we don’t want to be doing is to heat up the soil and outgassing a whole bunch of the same molecules that we’re looking to get.”

To avoid that problem, Lockheed Martin proposes a laser-based power-beaming concept to recharge lunar excavators in permanently shadowed regions. The company also sees nuclear fission power as critical to generating enough electricity to split water into hydrogen and oxygen in quantities sufficient to fuel crewed rockets to and from Mars—an important moneymaker in a future lunar economy, it says.

Lockheed Martin expects there to be many Moon mines by the 2040s digging up a couple of hundred metric tons of water per year. Ice processing and electrolysis separation of hydrogen and oxygen would be done at a central location.

Centralized infrastructure, including lunar habitats, would necessitate sturdy roads to enable travel to remote mining sites, particularly to avoid heavy-duty lunar rovers kicking up moondust or being bogged down in lunar sand. Thankfully, the lunar surface is not all dust.

“The upper part of it was very fluffy and low-density. It’s being continually stirred over geologic time by micrometeorite impacts,” Schmitt says. “But below that it is highly compressed.”

Because there is no atmospheric or water-based erosion on the Moon, all weathering on the surface is driven by meteorite impact and solar radiation, resulting in a mix of fine dust and coarser rock fragments. Larger rocks separated from the sandy regolith could be used as a sort of lunar macadam or gravel road, Schmitt proposes.

Thrust from the Apollo 17 Lunar Module’s single engine as it descended blew a 360-deg. sheath of dust away from the landing site, Schmitt says, adding that the particles disappeared over the horizon at a high velocity. While the Apollo 17 crews’ view on descent was not obstructed by a dust cloud, several other Apollo missions reported they could not see the surface as they touched down and that the debris interfered with landing radar.

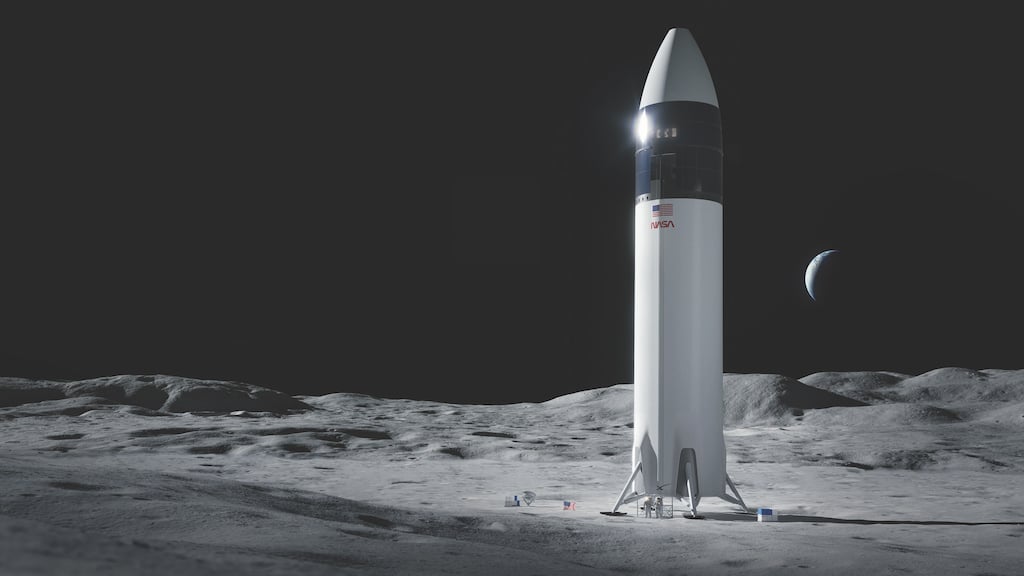

The problem could become worse with the Artemis program’s SpaceX Starship Human Landing System, which has six rocket motors, making its plume bigger and more complex. Interference between lunar missions, including avoiding plume surface interaction, is the No. 1 concern of Artemis Accord signatories, Pam Melroy, then-deputy NASA administrator, told Aviation Week in June (AW&ST July 1-14, 2024, p. 13).

“We’re starting to see some interesting science—some [of which] we knew actually from Apollo—that these particles stay suspended for longer periods of time than you might think,” she said. CLPS lunar landers have been equipped with cameras to study plume surface interaction, Melroy added. Lunar landing sites would need to be hardened with landing pads and blast-protection berms to prevent moondust clouds from damaging nearby equipment or habitats.

Regolith can also sneak into mechanical pieces, such as bearings and seals, grinding up and jamming components. “Quick-disconnects for various tools that we had [on Apollo 17] gradually froze up because of the dust,” Schmitt says. Using steel tools instead of aluminum ones ought to fix the problem, as the metal alloy is harder than moondust and would grind it up, he adds.

Dust easily finds its way into lunar crew cabins, too. Schmitt says he and fellow Apollo 17 astronauts tried to brush the regolith dust from their spacesuits prior to entering the lunar module but it was self-defeating, using up energy and embedding the dust deeper into the fabric. “The suit is your primary vector of dust into the cabin,” he says. To keep the cabin clean, Schmitt says spacesuits should be negatively charged to reject regolith, which also has a negative charge.

A similar idea is to be tested soon. NASA launched Firefly Aerospace’s Blue Ghost lunar lander to the Moon on Jan. 15 carrying two regolith test payloads, including an Electrodynamic Dust Shield demonstrator that might someday be able to repel lunar dust from spacesuits, helmet visors and boots as well as thermal radiators, solar panels and camera lenses. Blue Ghost is also carrying the Regolith Adherence Characterization payload, a sample of 15 materials—such as fabrics, optical systems, paint coatings, sensors and solar cells—to observe how lunar dust sticks to each surface.

“Dust is one of the biggest challenges from the Apollo era,” Nicola Fox, associate administrator of NASA’s Science Mission Directorate, told a Jan. 14 prelaunch briefing for the Blue Ghost. “It impacted the instruments onboard and the astronaut’s health when it got stuck to their clothes, and they breathed it in when within their spacecraft. Removing the dust will be revolutionary.”

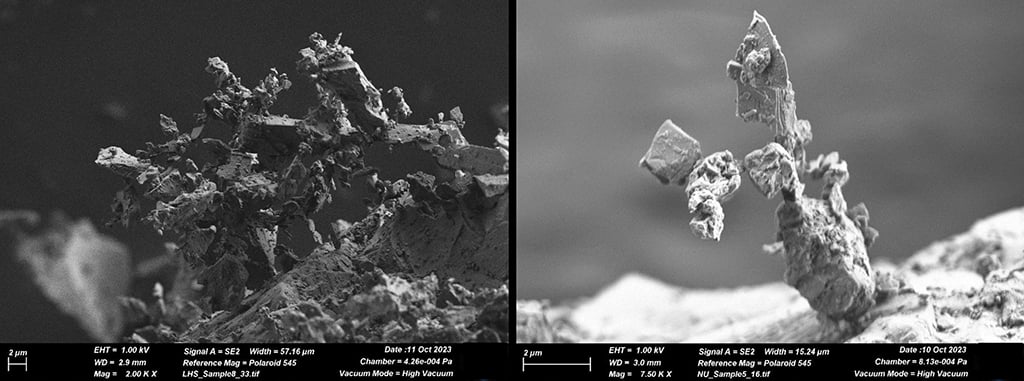

In fact, regolith is so sticky that it clings to itself in ways not typically seen with terrestrial sands, said Emma Quick, a modeling and simulations chemical engineer with Jacobs at NASA Johnson Space Center, who presented a paper at the AIAA Ascend conference. At the microscopic level, when observed with an electron microscope, regolith simulants create “fairy castles,” she said.

“Fairy castle structures are these complex, lacy, intricate structures that form when the particles are small enough and falling slowly enough that the intermolecular forces between the particles are stronger than the weight of those particles,” Quick said. “When this happens, you can get dust that sticks to itself with just one or two points of contact, rather than the typical three or more points of contact you have with something like gravel packing.”

These Van der Waals intermolecular forces make it extremely difficult to brush off or clean surfaces of regolith, she said.

Regolith is also extremely small—particles are 60-80 micrometers on average. Individual lunar regolith dust particles are typically made of sharp fragments of minerals and glass.

“The smaller particle sizes are actually the bigger problem. The smaller the particle size, the easier it is to get it into your lungs,” says Kim Prisk, pulmonary physiologist and professor emeritus of medicine at the University of California, San Diego. Prisk contributed to a European Space Agency research program on lunar dust.

Human lungs—even more so than skin—have the most exposure to atmospheric toxins, Prisk says, noting that the surface area of the lungs, if ironed out, would be about the size of a tennis court. “There’s a huge surface area, and the smaller the particle, the more easy it is to be carried by airflow.”

After returning from extravehicular activity on the Moon and removing their helmets inside the lunar module cabin, Schmitt and other astronauts experienced what he called “lunar hay fever,” such as sinus and nostril irritation, that dissipated after several hours. A flight surgeon back on Earth who retrieved spacesuits from the return capsule had a more severe allergic reaction to the moondust that worsened each time he was exposed to it.

Studies of rats exposed to lunar regolith and simulants have shown that regolith is not as harmful as freshly fractured silica, a substance found in some engineered kitchen countertops, but it is worse than nuisance dust. The risk is somewhere in between, Prisk says.

Yet studies on the health hazards of regolith typically use simulants or samples returned from the Apollo mission, that despite scientist’s best efforts, are not perfectly preserved. How deep into the lungs pristine moondust floating in the Moon’s one-sixth gravity might go and what its effect is on astronaut health after months of exposure are open questions, Prisk says.

“It’s not like it’s a showstopper, but it’s not something you’d ignore either,” Prisk says, noting that the Apollo crews did fine with relatively short exposures. “If we’re talking about six-month stays on the lunar surface, where you’re doing an [extravehicular activity] multiple times a week, each one of those is going to be an exposure. How much effort and how much mission cost do you have to put into mitigating that exposure to dust?”