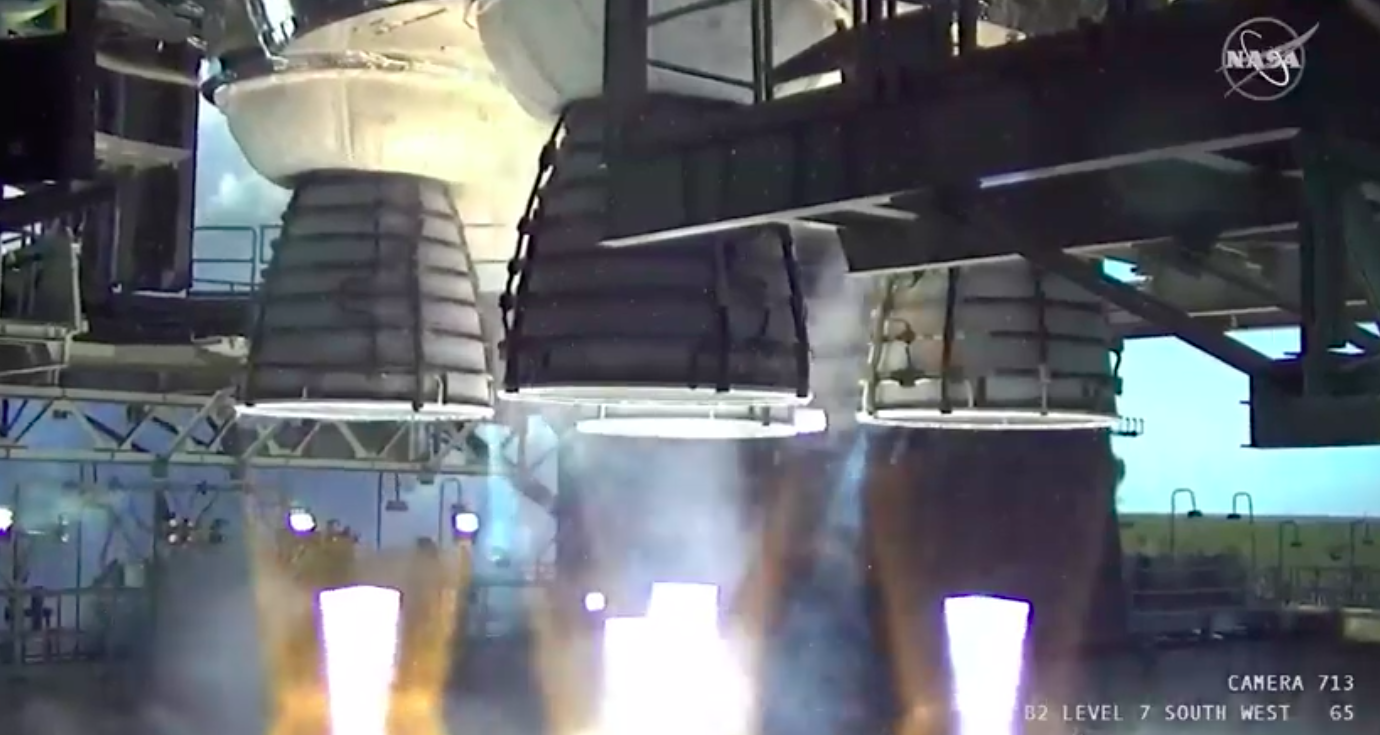

The 212-ft.-long core stage for NASA’s first Space Launch System (SLS) rocket ignited for a long-awaited static hot fire on Jan. 16, the last major test in a decade-long initiative to build a superheavy-lift rocket for human travel beyond low Earth orbit.

But the booster’s Aerojet Rocketdyne RS-25 engines, slated to burn for 8 min., shut down after about 1 min., raising the prospect of a second static engine test before the core can be shipped to the Kennedy Space Center in Florida for launch preparations.

If the test had gone as planned, NASA expected the Boeing-built core stage to arrive in Florida in February for launch in November on the Artemis I uncrewed Orion flight test around the Moon.

"We got lots of data that we're going to go through and be able to get to a point where we can make determinations as to whether or not launching in 2021 is a possibility or not," NASA Administrator Jim Bridenstine told reporters.

"This is an important day," he added. " I want people to be encouraged because the future is very bright."

John Shannon, Boeing SLS vice president and program manager, told reporters before the test that while the hot fire was planned for 485 sec., engineers needed about 250 sec. of run time to “have high confidence in the vehicle.”

NASA said it will take several days to comb through data collected during the test to determine why it was autonomously aborted about 1 min. after engine ignition.

NASA did not immediately say why the hot fire was cut off about 67 sec. after ignition, just after the first of a series of engine gimbal maneuvers.

The core’s four shuttle-era RS-25 engines roared to life at 5:28 p.m. EST at the B-2 Test Stand at NASA’s Stennis Space Center in Mississippi for the eighth and final milestone in the Green Run integrated test series. It was the first time the four engines, which flew a combined 21 space shuttle missions, were tested together.

Trouble surfaced a few seconds before the automated shutdown. A test conductor made a “failure identification call" on Engine No. 4. “That was shortly followed by an ‘MCF’—a major component failure,” NASA’s SLS Program Manager John Honeycutt said.

“I don’t know much more about that . . . at this point in time,” Honeycutt added. “Any parameter that went awry on the engine could send that failure ID, but at the time that they made the call, we did still have four good engines up and running at 109%.”

“When we got to main stage after we started the engines, part of the plan was to throttle back to 95% and then throttle back up to 109%," Honeycutt said. "At the same time, we're running a gimbal profile for all four engines, and so there are a lot a lot of dynamics going on at the point in time."

Around the time the engines began to gimbal, test engineers saw what Honeycutt described as “a little bit of a flash” come from an area between the thermal protection blanket and Engine No. 4.

“To the best of my knowledge, the engine controller sent the data to the core-stage controller to shut the vehicle down,” ending the test, Honeycutt said.

“In my opinion, the team accomplished a lot today. We learned a lot about the vehicle. We got the vehicle loaded; we got our pressurization system wrung out. We got the engines conditioned and got roughly 60 sec. of time on the RS-25s," he said.

The stage arrived at Stennis a year ago, but testing was delayed by work shutdowns due to the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic and a half-dozen hurricanes.

Editor's note: This article was updated with more information about the engine shutdown.