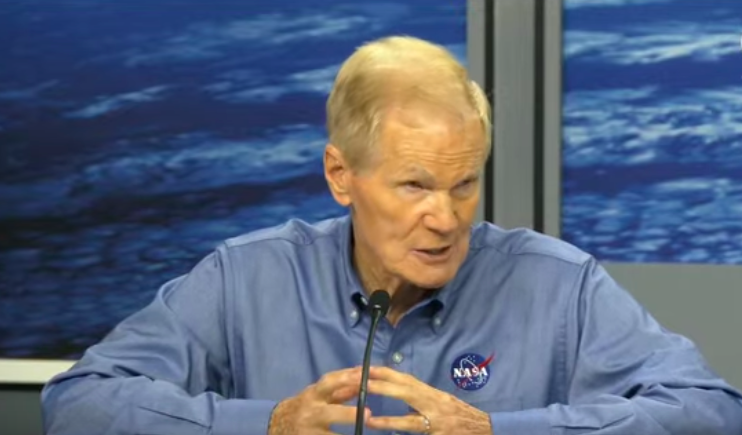

Mindful of the shuttle Challenger and Columbia accidents, NASA Administrator Bill Nelson announces the decision to bring the Boeing Starliner spacecraft home without crew.

HOUSTON and CAPE CANAVERAL—Two NASA astronauts conducting a flight test of Boeing’s CST-100 Starliner spacecraft will return to Earth in February aboard a SpaceX Crew Dragon amid lingering questions about Starliner's propulsion system, the agency said Aug. 24.

“We have had mistakes in the past,” NASA Administrator Bill Nelson told reporters at Johnson Space Center in Houston. “We lost two shuttles as a result of there not being a culture in which information could come forward. Spaceflight is risky, even at its safest and most routine, and a test flight by nature is neither safe nor routine. [This] decision … is a result of a commitment to safety.”

Veteran astronauts Barry “Butch” Wilmore and Sunita Williams lifted off on June 5 for what NASA and Boeing hoped to be an 8-14 day Crew Flight Test (CFT) of Starliner, a final milestone ahead of Starliner’s certification to join SpaceX’s Dragon in ferrying astronauts to and from the International Space Station (ISS.)

But during Starliner’s automated approach to the ISS on June 6, five reaction control system (RCS) jets were sidelined by the flight control software due to what was later determined to be overheating. All but one of the jets were recovered and Starliner was able to make an automated docking one orbit later.

The thruster problems followed a series of small helium leaks in the system that pressurizes Starliner’s RCS and larger maneuvering jets. Two months of extensive testing and analysis followed. Wilmore and William remained aboard the ISS while NASA and Boeing mulled options.

Starliner will now be reconfigured for an uncrewed, autonomous return to Earth, possibly in early September. Wilmore and Williams will be reassigned from the CFT to join the upcoming SpaceX Crew-9 mission, which will launch with a two-member crew rather than the previously planned four, and return in February 2025. NASA did not announce which Crew-9 astronauts will be dropped from the flight, which is targeted to launch on September 24.

“Uncertainty remains in our understanding of the physics going on in the thrusters,” NASA Associate Administrator Jim Free said. “We still have some work to do.”

The decision follows an agency-wide Flight Readiness Review (FRR), with NASA participants unanimous in their support for the Crew-9 Dragon option.

"Our intent today was to have the first part of an FRR. The goal of that review was to come up with a NASA recommendation on whether we should proceed with the CFT either crewed or uncrewed," said Ken Bowersox, NASA associate administrator for space operations.

"Our Boeing partners told us they would be able to execute either option. They thought the call belonged to NASA because of our wider view of all the risks involved. We conducted a poll of all our organizations. They thought we should proceed uncrewed with the flight test. So our next step will be to progress toward that uncrewed flight test."

The uncrewed deorbit plan will be finalized following a second FRR Aug. 28-29.

While the biggest demand on the thrusters was during the approach to ISS, the system will be needed again to hold the vehicle’s orientation for the deorbit burn and to maneuver for the separation of the crew and service modules for re-entry. “We just don’t know how much we can use the thrusters on the way back home before we encounter a problem,” Bowersox says.

“We are clearly operating this thruster at a higher temperature at times that it was designed for,” added NASA's Commercial Crew Program Manager Steve Stich. “Could a thruster just fail off gracefully, or could there be another failure mode that is not so graceful. That was an important factor.”

Recent analysis also uncovered higher-than-expected heating in one of the propulsion system pods, known as doghouses, raising additional uncertainties, Stich noted.

Following a call with newly named Boeing CEO Kelly Ortberg, Nelson said he is “100%” sure Boeing will fly Starliner with crew again. “He expressed to me an intention that they will continue to work the problems once Starliner is back safely, and that we will have our redundancy in our crewed access to the space station,” Nelson said.

NASA in 2014 selected Boeing and SpaceX to develop, test and fly ISS crew transportation systems. SpaceX completed flight tests and began operational crew-rotation missions in 2020. Boeing’s Starliner has had a series of technical issues that required a repeat uncrewed flight test in 2022 and several delays ahead of CFT.

“Boeing continues to focus, first and foremost, on the safety of the crew and spacecraft,” the company said in a statement. “We are executing the mission as determined by NASA, and we are preparing the spacecraft for a safe and successful uncrewed return.”

All of the propulsion components of concern are located in Starliner's service module, which is located behind the crew compartment and developed to be jettisoned destructively into the Earth's atmosphere before the crew capsule reenters the atmosphere with the astronauts for the final leg of their descent.

Once the capsule docked to the ISS, NASA and Boeing initiated ground- as well as Starliner-based tests and modeling of the two concerns. An identical, unflown thruster assessed in the ground testing at White Sands, New Mexico, showed signs of a bulge in a Teflon seal in the oxidizer system that restricted the propellant flow in a way that matches the Starliner's inflight performance. The onboard ISS analysis included Starliner RCS thruster firings, which augmented the informative findings from White Stands, according to Bowersox and Stich.

Each of the findings will help Boeing modify the RCS operations to better control the thermal performance of the thrusters and thruster housing, Stich explained during the briefing.

As they have throughout their extended mission to date, Wilmore and Williams are to continue participating in the research and maintenance activities underway aboard the ISS and possibly participate in spacewalks.

"I talked with Butch and Suni both yesterday and today. They support the agency's decision fully, and they are ready to continue their mission on board the ISS," Norm Knight, NASA's director of flight operations, told the news briefing. "Their families understand. I'm not saying it's not hard. They are doing well and they understand."

Both Wilmore and Williams were U.S. Navy test pilots before their selections by NASA to train as astronauts. Prior to the CFT, Wilmore had accumulated 178 days in space over two missions to the ISS. Williams had logged 377 days over two missions to the ISS.