As with other professions, the normal progression for a pilot on the way to becoming a professional aviator means earning progressively higher and higher levels of certificates and ratings. The start of this long journey begins with your first medical certificate. On it, it says clearly, “Student Pilot.” You definitely know where you stand with this one in your pocket. Once you earn your private, you start on your instrument rating or commercial. Once you earn your commercial, you earn a multiengine rating. Then you build hours for your airline transport pilot (ATP) license. Then, once you earn your ATP, you think you’ve arrived.

But even with that achievement, no one (no insurance company that is) will let you sit left seat in a heavy jet just yet. Why? Because for all intents and purposes, you are still a student pilot! Ironically, we all began as students hoping to graduate to our professional lives. But lost on many of us is the fact that our apprenticeship never ended. We will always be students, so we might as well learn to be better students.

Step One: Be a Better “Forever Student”

In my 20-year U.S. Air Force career, I spent 15 years as a pilot and five years flying a desk. While on the Air Staff at the Pentagon I was cautioned to never take work home with me. “It will destroy your marriage and it will destroy your passion for your profession.” We never had such a warning while out in the field, flying airplanes. At the squadron level, it was a badge of honor to live, think and breathe aviation. With that background, it continues to amaze me to hear my fellow civilian pilots talk about having a distinct line between work and home. I might be wrong here, but in my view, your aviator mind should never switch off. Flying airplanes has become safer over the years, but it is still not risk free. There comes a time where you have studied enough and any more becomes counterproductive. But until that point, getting better at what you do makes you a safer pilot. It has become easier to immerse yourself in all things aviation.I usually start each day with a series of emails from various aviation websites and magazines and filter through to read those that apply to my aircraft type (Gulfstreams) and my operation (international business aviation), and then I include any others that are just interesting on their own. A few of my favorites:

- BCA magazine

- Ops Group

- Curt Lewis and Associates Flight Safety Information

Being a forever student aviator does tend to monopolize your attention and you do have other things to worry about. But that is part of the challenge: striking the right balance. Just because you are a forever student, however, doesn’t mean it can’t be entertaining. I trade book recommendations among friends and keep a list of my most recent top-10 titles:

(1) Gandt, Robert, Skygods: The Fall of Pan Am.

(2) Goldstone, Lawrence, Birdmen: The Wright Brothers, Glenn Curtiss and the Battle to Control the Skies.

(3) Copp, DeWitt S., Forged in Fire.

(4) Gann, Ernest K., Fate is the Hunter.

(5) Coram, Robert, Boyd: The Fighter Pilot Who Changed the Art of War.

(6) Wolfe, Tom, The Right Stuff.

(7) Gawande, Atul, The Checklist Manifesto: How to Get Things Right.

(8) Hansen, James R., First Man: The Life of Neil A. Armstrong.

(9) Weatherbee, Capt. Jim, USN Retired, Controlling Risk in a Dangerous World.

(10) Marquet, L. David, Turn the Ship Around!

Each book will make you a better aviator. The list is forever changing and can spark intense debate. But that is part of the fun of being a forever student aviator. I still cling to hardcover copies of each book, just as I continue to cling to DVDs of my top-10 movies:

(1) “Twelve O’Clock High” (1949)

(2) “Catch-22” (1970).

(3) “The Right Stuff” (1983).

(4) “Dr. Strangelove” (1964).

(5) “The Red Baron” (2008).

(6) “The Great Waldo Pepper” (1975).

(7) “Airport” (1970).

(8) “Memphis Belle” (1990).

(9) “Flying the Feathered Edge” (2014).

(10) “Airplane!” (1980). [“Surely you can’t be serious!” “I am serious, and don’t call me Shirley.”]

Step Two: Do a Better Job Preparing for Class

If you are like me, you invest a lot of effort into your recurrent training every six months, and once you are done, you want to give yourself a break from regular study. You promise to get back into it after a month, but before long it is six months later, and you show up for another recurrent ill-prepared. I say, “like me,” meaning “like the used-to-be me.” I now have a 30-day preparation routine. The core of the idea is to devote an hour each day to a well-thought-out study plan, starting 30 days before class. Limiting yourself to an hour will encourage you to keep at it until you are complete. Here is my current plan when preparing for Gulfstream GVII recurrent:

(1) Class Day Minus 30: Review memory items daily with audio and iPhone flash cards.

(2) Class Day Minus 29 through Minus 19: Devote remainder of hour studying a different major aircraft system each day.

(3) Class Day Minus 18 through Minus 13: Devote remainder of hour studying a different normal procedure.

(4) Class Day Minus 12 through Minus 4: Devote remainder of hour studying a different abnormal or emergency procedure.

(5) Class Day Minus 3 through Minus 1: Devote remainder of hour studying the theme you expect to see for each of three simulator sessions.

I say this is my “current plan” because it evolves after each recurrent training class.

Step Three: Take Better Notes

I spent my first 10 years of attending regular recurrent training taking notes the same way I did in college. I listened and jotted as quickly as I could, sometimes to the point where the result was indecipherable as soon as I put my pen down. The notes proved useful in college, as there was a project or paper coming due and I was forced to look at them the next day, if not sooner. There was no debate on the content because the person doing the talking was usually the person doing the grading. Besides, we were not talking about life and death, just an end of semester grade.This method has failed me as a pilot at initial, recurrent or any other aviation-related training. The person doing the instructing is delivering information-dense material and normally using information-dense slides that whip by faster than I can write. I once resorted to using an audio recorder until I was reminded that was verboten in the training contract. I even took iPhone photos of some of the slides--until once again reminded it was proprietary information. Looking at our latest training bill, I think spending more than $100,000 for a single pilot’s recurrent ought to entitle us to a camera and audio recorder in class, but those are the rules.

The solution came to me about 10 years ago. It is a note-taking method developed in 1962 by Walter Pauk, director of Cornell University’s Reading and Study Skills Center. His book, How to Study in College, is in its 11th edition and worth the investment. The crux of the method is to draw a vertical line on the left side of your notepaper that extends from the top to about an inch or two short of the bottom. Then line off the bottom with a horizontal line. The left column is for your cues, the right column is where your notes go, and on the bottom is a summary.

As you sit in class, you listen first, take notes second. The notes go into the right column using short sentences and the only thing you need to record verbatim are exact numbers or items required to be exact. You then write cues in the left column that further summarize the notes or remind you of questions that need answers. You can do this during class, break or after class. But the sooner the better. Finally, after class, you summarize it all. That is the method in a nutshell. I add to the method by further research, usually added in a different color.

You can buy “Cornell notes” paper pads on many campuses and even online in colorfully bound books. My method of choice is on an iPad using the “Noteshelf” application, available for $9.99. The app includes a Cornell notes template.

Image credit: James Albright

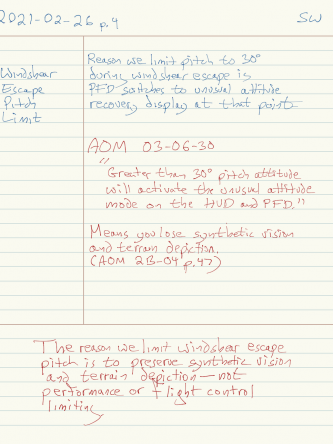

One of the advantages of using an iPad notetaking application is there is no cost for wasting “paper” and I can devote a page to each thought, which improves the future use of the notes. I have my own customized style with each note. On the example page, I note the date and page number of the note on top, to the left. I write the instructor’s initials on the right. The note and the cue are written during class in blue.

During a recurrent training class, the instructor said the reason why we GVII pilots are supposed to limit our pitch during a windshear escape maneuver is to prevent the primary flight display (PFD) from going into an unusual attitude display. I thought it had to do with a performance limitation or perhaps to prevent the flight control computer from taking over in one of its protective modes. That night I researched this further and entered my findings in red.

I can now easily find the answer to this question, know where I first heard it, know the source material, and know who gave me the information in the first place. Over the years I’ve found some instructors are simply repeating things they’ve heard without any further foundation. After some research I was able to refute the knowledge and let the instructor know. You may have a better method or this might be just what you’ve always needed. But if your notes end up at the bottom of a shelf never to be seen again, I encourage you to give the Cornell notes method a try.

Editor's note: This is the first of a two-part "Being a Better Student" article. Here's part two.

Comments