Most of our training as captains comes from our time as crewmembers watching captains in action. The effectiveness of that training depends greatly on the effectiveness of the captains we observe. Ideally, we will serve an apprenticeship with both good and bad. If you learn only from good captains, you may assume your captaincies will be easy and you will be ill-prepared for the challenges to come. If you learn only from bad captains, you are at risk of what I call “the tormented become the tormentors” syndrome. The problem boils down to a question of authority. Some captains assume the authority bestowed by the rank of captain has no limits and is the answer to all disputes. Other captains believe in a pure democracy and that no decisions are above a crew vote. Clearly there is a balance needed.

A trendy topic among human factors scientists is “trans-cockpit authority gradient,” or TAG. The idea is that the captain has an authority that comes from sources beyond the title. It can be perceived from the captain’s age, experience, proficiency, confidence, physical size, assertiveness or any other factor we can think of as “gravitas.” We are told that this authority gradient can be too steep, flat, reversed or optimal. I think once again the scientists have made something simple too complicated.

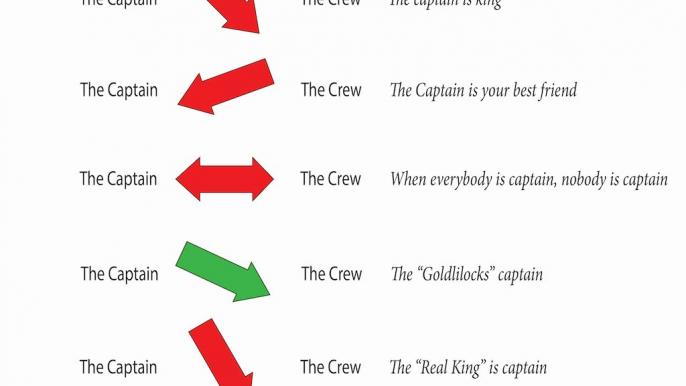

Before the days of CRM, a common model was what the human factors gurus call a steep authority gradient; I call it the “captain is king” gradient. You will still find this at airlines with large seniority gaps and pilots who are hyper aware of their line numbers. While strong unions can protect first officers from tyrannical captains, there remains the fear that a bad review from one captain can spread to the chief pilot and other captains. Smaller flight departments can be at even greater risk, where the captains may have leadership positions that can determine a pilot’s pay, bonus, or even continued employment.

On the opposite end of the scale is the reversed authority gradient, where the captain cedes all authority. I call this the “captain is your best friend” gradient. While you can find best-friend captains in any environment, small flight departments are at greatest risk. If the small crew force has been in place for a while, captains may be reluctant to exercise any authority that can be unpopular. A decision to divert, for example, can be overridden by the desire to get the first officer home for a child’s little league baseball game.

Somewhere in the middle of the king and the best friend is the flat authority gradient; I call this the “when everybody is a captain, nobody is a captain” gradient. The danger is that when a captain has a reputation for always ceding decisions to the crew, there comes a point in time where the captain needs that authority for a particular situation, but the crew may not wish to give it back.

I think it is obvious to most effective captains that the correct authority gradient, the “Goldilocks gradient,” is with the captain exercising final authority but still inviting crew input, considering crew inputs when offered, and explaining decisions that overrule the crew’s wishes. What is less obvious and rarely discussed is what happens when the captain’s organizational boss or a charismatic, informal leader is a part of the crew. The “real king is here” gradient can be the worst kind of gradient if the real boss fails to allow the captain to act as a captain. I found myself in this position many times and have learned from experience it takes an active effort to prevent this gradient.

Consider two pilots getting an aircraft ready for the day’s trip. The first officer is the flight department’s director of aviation and the one who turns in an end of year evaluation and recommends pay raises and bonuses. The other pilot is a fully qualified and properly designated captain for the trip but also works for the first officer. If the mechanic approaches the first officer for direction on a maintenance deferral and the first officer/director of aviation decides, the captain’s authority is compromised, and the tone of the trip is set off in the wrong direction.

The answer to all these gradient problems is simple: Stay within your boundaries. Everyone has a role to play and when everyone plays their role, life becomes predictable, simple and safe. The key role, the starring role, is played by the captain.

Being Better

In this series about being better, we have discussed how to be a better student, pilot, crewmember and captain. Each skill lends itself to all crew positions, especially the captain’s. A non-aviator may look at these suggestions and argue they apply equally well to all professions requiring a high level of skill and teamwork. And that is true. It all combines into the next and final article in this series: “Being Better.”