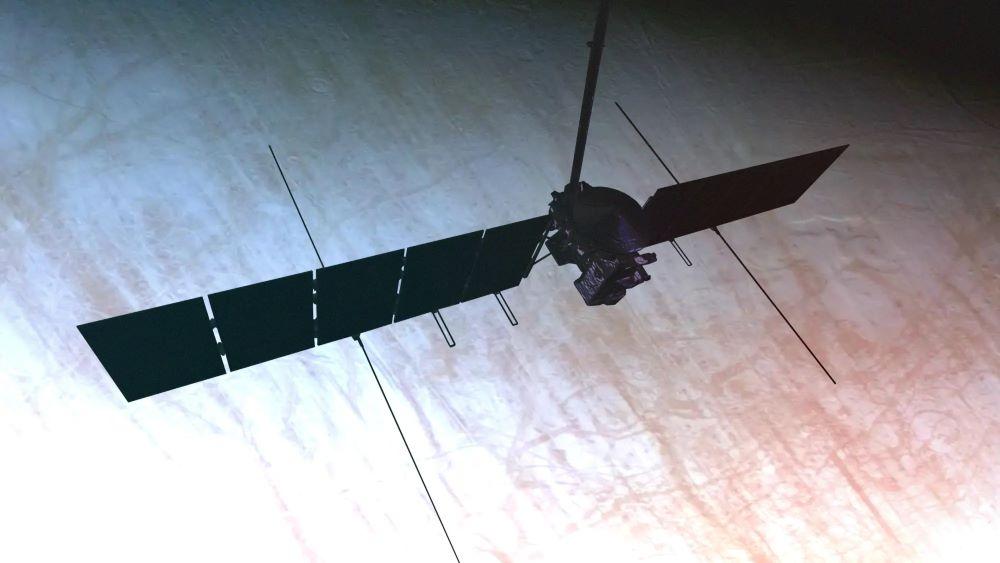

Europa Clipper

Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech

The largest spacecraft ever launched on a planetary mission, NASA’s Europa Clipper is doing well and speeding along toward the first of two gravity assists intended to achieve a 2030 arrival at Jupiter, a NASA update says. Launched Oct. 14 atop a SpaceX Falcon Heavy, the $5.2 billion mission will...

Subscription Required

NASA’s Europa Clipper Is Off And Running is published in Aerospace Daily & Defense Report, an Aviation Week Intelligence Network (AWIN) Market Briefing and is included with your AWIN membership.

Already a member of AWIN or subscribe to Aerospace Daily & Defense Report through your company? Login with your existing email and password.

Not a member? Learn how you can access the market intelligence and data you need to stay abreast of what's happening in the aerospace and defense community.