Podcast: Deep Dive Into The Mysterious X-37B Spaceplane

As the X-37B graces the cover of Aviation Week & Space Technology magazine, editors discuss the unique characteristics of the spaceplane and what its up to as it orbits Earth.

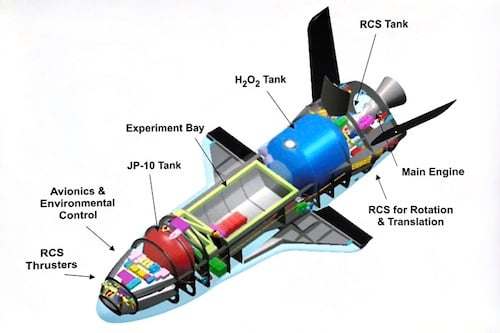

Check out the X-37 graphic Guy describes:

Subscribe Now

Don't miss a single episode of the award-winning Check 6. Follow us in Apple Podcasts, Spotify or wherever you listen to podcasts.

Discover all of our podcasts at aviationweek.com/podcasts

Transcript

Robert Wall:

Welcome to Check 6, where this time we have a particularly exciting topic for you, the Pentagon's X-37B military spaceplane, but about which we know relatively little. One thing we do know, it's pretty cool.

While the X-37B itself isn't classified, the DoD has kept largely quiet about much of what it does with that spaceplane. In this week's Aviation Week magazine, we lift the curtain a bit on that project.

Joining me today to put the spotlight on the program are Vivienne Machi, our Military Space Editor, and Guy Norris, the Senior Editor for Aviation Week. I'm Robert Wall, the Executive Editor for Defense and Space, and your host for today.

Vivienne, first of all, congratulations. Great story. And more importantly, making your first appearance on Check 6. Really sorry it's taken so long, but it's great to have you here. And what a wonderful topic to kick it all off. Why don't you start us off a bit and describe to our listeners who may not know what the X-37B is, what it does, and more importantly, how the U.S. military is using it.

Vivienne Machi:

Thanks, Robert. Happy to be here and to talk about, yes, quite a mysterious but exciting topic. So the X-37B is probably one of the more mysterious but somewhat open programs that the U.S. military has going on right now. It's a spaceplane that is derived from NASA originally, but now operated by the Space Force. The Air Force took it over it in 2006.

It's a little less than 30 feet long and looks like a little tiny spaceplane, exactly kind of how you would imagine one. And it's pretty cool because it's launched aboard a rocket kind of on the side of it, and then it operates in space and then it autonomously lands on a runway like a plane, and it's the only spacecraft that we have that can do that. So that in and of itself is pretty cool. It's also reusable.

We know of at least two of them. We don't know if there are more, but there are at least two. And the Space Force is able to pretty quickly refurbish them and get them back up and running afterward, which is also very interesting.

So it has been on seven missions so far. It's currently operating its seventh mission. As of today that spaceplane has passed 420 days in orbit, and that's not even really impressive for the X-37B. Its longest mission so far is 908 days on orbit. So this current mission is the second shortest mission that it has so far.

I think what makes the spaceplane the most interesting is it carries experiments into orbit and the Space Force is using it not only itself as a test bed using the spaceplane itself to test high-radiation environments and long duration in orbit, but it's also carrying payloads, most of which we don't know about, into orbit, testing them, and then bringing them back to earth. So that is also a very nifty capability that the Space Force has.

Robert Wall:

Guy, I mean, you've been following this program for a long time too, and just to be curious. I think everyone who knows about it is slightly fascinated by something else. So what struck you particularly?

Guy Norris:

Thanks, Robert. I mean, you're right. As Vivienne says, this was originally NASA program. And I think what's amazing about it is the fact that then, as Vivienne mentioned, it's a small spaceplane. Its dimensions, its wingspan, for example, 15 feet is designed to fit within the original program, which was the space shuttle bay. Because the original plan was to see if it could launch it either on a rocket or within the shuttle cargo bay.

But what I think about when I think about where it's come from, you know, NASA originally wanted to develop a reusable space capability, reduce the cost to get access to space. I don't know if our listeners might remember the DC-X program. I don't know if you remember that, but it really paved the way for what Elon Musk has been able to achieve with SpaceX and the reusable Falcon Series and Starship now. But it allowed this, it proved that you could actually bring a rocket back to landing.

So when that finished, NASA thought, well, what's next? And they came up with this program called the Future X Pathfinder, and there were two vehicles that came out of that. One was X-34, which kind of looked very much like the X-37 and the X-37A. Now the X-37B that we know and love, or at least we'd like to know more about it, but it's X-37A was the original version that NASA produced. It was slightly shorter than the one, the X-37B, which Vivienne's described, but it was really the progenitor for the series. And the great thing about it is that it really brought about the advent of a vehicle that could not only be reusable, it would come into land autonomously, but it could also do weird things in space itself. You know, it could actually maneuver in space and this is not, and it was able to do this by using the wings essentially very low altitudes, so in the upper reaches of the atmosphere. And I think we can unpack that a little bit and the benefits of that from a military perspective coming up. But those are the two features of it.

And just before I pass it back to you, one of the incredible things about it is, and again, Vivienne mentioned this, the longevity of the missions originally wasn't designed for anything like that. NASA was sort of thinking maybe 20 days, that sort of thing. I remember talking years ago to one of the original designers of the X-37A. We're sitting around the dinner table at this conference and he goes, he says, hey, do you follow the what's going on with the Air Force's X-37B? He goes, what are they doing with it there? I said, well, I've no idea.

It's classified. You know? We don't know. And I said, why do you ask? He says, well, I was one of the designers and I was always worried about it because when they extended the mission up to 270 days at a time, I'd never thought about out gassing on the tires. He said, the wheels are sitting there in the undercarriage bay. What happens if they're flat when it comes back to land at 200 miles an hour into Vandenberg. It's going to go straight off the runway. So he said, I've had sleepless nights worrying about it. Obviously they did take care of that and it's been fantastically successful.

Robert Wall:

Yeah. Tremendous. Vivienne, maybe tell us about what your sense is - again, we may not know exactly what they're doing up there with the vehicle - but you have a good, I think a decent sense now from talking to folks of strategically what the objective is that the Space Force is looking to get out of this.

Vivienne Machi:

Interestingly enough, I would say, it's not that different from NASA's original mission in that they are really wanting to continue using it as a testbed, an experimental spacecraft that can help the Space Force that can inform them about how other such vehicles in the future can operate in space.

And I think it's a good time to take a step back and see where the Space Force is in this time and space in this era. Military officials are talking quite a bit these days increasingly about competition among the stars. We no longer have the higher ground in space. China and Russia and others are trying very quickly to catch up with us, and some would argue that China and Russia are already there.

And the Space Force was stood up really to help the U.S. learn how to fight wars in space. Now we never have fought a war in space, so that's kind of hard to figure out how to do. But platforms like the X-37, officials are now saying, can really help provide the data that they need to understand how to maneuver in space. Senior military officials are talking a lot about a concept called dynamic space operations in which there's increased mobility among the stars. And to Guy's point, the increased maneuverability of the X-37B provides them with tons and tons of data about how its specific characteristics might be applied to different platforms going forward.

Robert Wall:

Yeah. Very interesting. I mean, if someone now goes back who doesn't know and is interested in X-37B and Googles it, probably one of the things I'm going to stumble across is one of the few things that Pentagon has said about it, and actually quite recently, is that it used the X-37B or had it perform an aerobraking maneuver. So Guy, what in God's name is an aerobraking maneuver?

Guy Norris:

Right. Well, yeah, aerobraking, it sounds a bit like what it is using the air to brake. It's using the upper atmosphere to actually cause drag on the vehicle. You would think in space there is no drag, there's no atmosphere, but there is if you get low enough. And so one of the things that in fact, Boeing put out a pretty good video on this about how it works. But essentially if you imagine that the spacecraft is put into a highly elliptical orbit around the Earth, and if it's very elliptical, it's the highest point of that, that means that when it comes into its lowest point of the orbit, which is the periapsis, I suppose, or the point of perigee in this case, the resulting drag really slows the spacecraft down.

Now it's weird actually because it's not the first time. This is a well-known technology. There's nothing kind of particularly secret about it. In 1991, for example, the Japanese were the first that we know of anyway, to use it as a maneuvering system to put the spacecraft through the low earth orbits to change its orbit. And in 1993, for example, the Magellan spacecraft did the same maneuver using the atmosphere to for extra drag, and then it changed the orbit.

But why is it great? It's good for at least three reasons, and this is why the Space Force is able to make the most of this because, first of all, it saves fuel. It's massive saving on propellant for maneuvering. You don't have to use the onboard thrusters. It enables you to do these orbital adjustments, which means that it can come in at a slight, at this angle and pop out at another. Which means that if you are a Chinese for example, and you're trying to figure out what's happening, you might lose it for some time in orbit. It'll take you a while to pick it up again because it's very unpredictable from their perspective. The other thing is it can be used, and this is what was actually demonstrated. You can de-orbit modules, for example, and get rid of the space debris problem because you can dig into the atmosphere, drop off the space debris, and let it de-orbit from that.

Now, we've even seen Hollywood use it. Who remembers the movie Interstellar? Matthew McConaughey, who played Cooper, the astronaut pilot, he actually used aerobraking to slow the spacecraft rangers. So there you go... the wormhole. But anyway, we digress. But from a military perspective, the ability to do to do this is absolutely essential because it uses the extra dimension of the wingspan. Obviously the bigger, you know, those early spacecraft were just spacecraft. They didn't have wings. But if you've got a wing as well, you get a lot more aerobraking performance 'cause you've got a bigger wetted area. You can produce more drag.

And of course, the other thing about the shape is that once you get back into the sensible atmosphere, you're able to use this ability to extend cross range, which of course the space shuttle famously did, which means that you can land at a different place and you can extend, the options for landing are dramatically increased by hundreds of miles. And of course with the Shenlong spaceplane coming in from China, these are directly the sort of characteristics you need to not only have but to demonstrate day to day use of.

Robert Wall:

Yeah. I mean, glad you brought that up actually. And Vivienne obviously touched on this as well, but I think it's probably useful to talk a bit more about what other people are doing in this area specifically. And then perhaps also maybe, Vivienne, we chatted about this a bit, how the Air Force is thinking about this. I mean, my suspicion as much of what the X-37B's been doing has been doing is low Earth orbit. I could be wrong. But I'm wondering what the Space Force's ambition is to beyond that.

Vivienne Machi:

Yeah. So our understanding is that up until this current mission that the X-37 has been on since December, 2023, its seventh mission, up until then, it's really only operated in low Earth orbit. And this seventh mission is the first one where it changed to operating in a highly elliptical orbit. So that in and of itself was a novel development for the X-37B. Again, like I said earlier, we don't know too much about the specific payloads aboard any of these missions. The Space Force has revealed a couple of them every so often. For example, right now, we do know that there's a NASA science mission aboard, but there's definitely other things that we're not aware of. But they have mentioned in general terms that it is performing space domain awareness missions, testing, I should say, for example.

Robert Wall:

Which is for those who aren't steeped in Space Force lingo, what is that?

Vivienne Machi:

So space domain awareness is having awareness of everything in space. So it's being able to view, to catalog, to track pretty much any manmade especially, but really any object in space. So that contextually to this, if you're maneuvering, you know what you might run into, what might run into you, you know what might be watching you. So it's really one of the most critical mission areas for the Space Force going forward.

Robert Wall:

Sorry. Guy, what are you showing us?

Guy Norris:

Yeah. For our listeners who can't see this, unfortunately, but what I was kind of emphasizing here is a graphic showing the insides of the X-37A, which of course for a classified program in these days, you would never have one of these, but it just sort of shows that where the roots of the program came from. So although we don't know much about obviously what the vehicle is doing, or we do at least know what the building blocks of it are for the B model, which Boeing built two of it, as Vivienne mentioned. And I think it's worth it pointing out that we're going to be looking at this.

I mean, the program for the Air Force is from the, now, the Space Force perspective is it's 20 years old, which comes to your question about what next. So I mean, for example, I think all but the test vehicle was officially started in November of 2006 when the Air Force announced it was going to be doing its own version of it. And the second one, I mean Boeing began work on the second one in 2010, and it made its first mission in 2011. So this is a vehicle that's relatively old in its respect, in that respect. And I think it's worth looking at maybe some of the propulsion systems. So I'm going to show the graphic again so you guys...

Robert Wall:

By the way, Guy, we're going to make you share that graphic with our listeners and put it in the show description.

Guy Norris:

Absolutely. Yeah. Okay. So it shows sort of a twin fin small kind of almost like mini space shuttle, but with the system sort of Rocketdyne AR2 three rocket in the back end. And it uses, it's also able to deploy solar power arrays, gallium arsenide solar cells with lithium ion batteries to extend that mission capability out to those incredible lengths that Vivienne mentioned. And the other interesting thing about it is, and the reason that when it lands at Vandenberg, you have these people in their protective suits, is it's sort of got this hypergolic thruster system. It uses this JP-10 fuel. It's a synthetic fuel that absorbs heat energy, so it's endothermic, but it's got huge high energy density. So ideal for military applications and it's a pretty cool piece of kit. But what really needs to, well, I think what the Space Force needs to be doing is thinking, well, okay, we've proved this works. It continues to work. Where do we go from here?

Robert Wall:

Yeah. So thanks. That was basically where I was going to go next. I mean, there are plenty of black programs out there we know of. Well, we know they exist. Many we only know because contractors keep having cost overruns on them and we don't know exactly what they are. But do we have any sense either whether there is something else underway already or do we have a sense of, Vivienne, maybe where the Space Force might want to go?

Vivienne Machi:

So related to the X-37B specifically, when I interviewed the Chief of Space Operations, General Saltzman, a few weeks ago, I asked him what sort of operational plans there might be for the X-37B or a similar spacecraft. And he told me that any of those conversations are still very early in the research and development phase and left it at that. But I will say he did tell me too that the spaceplane is expected to play a very big role in informing the Space Force's capability development again for future spacecraft. So over the next month, the Space Force is standing up a new command called Space Futures Command, and this command will be responsible really for helping the Space Force design their future.

It's going to do war gaming. It's going do testing. It's helping to shape the mission areas that the Space Force will be focusing on going forward. And General Saltzman said that the X-37, the data coming off of the X-37B will be shared directly with Space Futures Command and they will use it to do their war gaming, to do their testing. And then on the other side, the Space Futures Command will be sharing their data back to the Space Force, back to the Rapid Capabilities office in order to better inform how they can use the X-37 on orbit, sort of in a symbiotic relationship. So that's what we know for now.

Guy Norris:

Yeah. And Vivienne, can I ask you this? You've been writing about the space nuclear propulsion side like I have as well over recent years. In DARPA or with the DRACO program, there's now been a few question marks over where that's going in terms of the schedule. But what do you think? Do you think that could be one possible avenue? I mean, this could prove, we've seen how using a conventional type of propulsion system and combine that with aerobraking and the use of solar cells, they've been able to produce this amazing combination. But imagine if you replace that conventional thruster and system and rocket power with nuclear for in space propulsion. That could be quite a game changer. Couldn't it?

Vivienne Machi:

Yeah. Honestly, I hadn't even thought of that. So that's a great idea. I think you should send that to the RCO and then see what they think. But certainly, deep space exploration, cislunar exploration is a huge area of focus for the Space Force as well as the commercial area. So I mean, from my view, that seems like a nice natural fit, but we'll just have to wait and see.

Robert Wall:

All right. Well, why don't we wrap the episode there. Thanks to our listeners for checking out another episode of Check 6 and thanks Vivienne and Guy, and also to our managing editor in London, Guy Ferneyhough for producing this episode. Definitely check out Vivienne's article in Aviation Week and Space Technology. And if you haven't already, be sure to subscribe to Check 6 so you would never miss an episode. And if you find this discussion as helpful as you probably do, please leave us a rating or review wherever you listen to your podcast. Better yet, share this episode with a friend or a colleague. That's it. Bye for now.