More than 11,000 aircraft retirements are expected over the next decade, according to Aviation Week Network’s 2019 Commercial Fleet & MRO Forecast, but what will become of aircraft that reach the end of the line? There is plenty of value to be extracted from a retired aircraft, ranging from intact engines to raw metals and alloys.

According to aircraft disassembly specialist eCube Solutions, more than 90% of an aircraft’s components can be reused or recycled, and a recent report from Research and Markets forecasts that the market for salvaged aircraft components is expected to surpass $3 billion in 2027. Read on as Aviation Week takes a look inside everything happens between an aircraft being selected for disassembly and its raw components being recycled.

Reaching The End Of The Line

The determination of when it’s time to scrap out an aircraft can come down to a number of factors, ranging from age or cycle count of parts to the number of needed repairs. According to Mike Corne, director of eCube Solutions, operators and lessors ultimately try to determine whether it is financially worth continuing to invest in aircraft as they age.

“In certain cases, the engines can actually create more value for the owner than the entire aircraft because there’s such a high demand for certain engine types,” says Corne, adding that in most cases engines comprise approximately 80% of the value of the aircraft.

Breaking It Down

Once a decision is made to scrap out an aircraft, its first stop is with an aircraft or engine teardown specialist, where each of the components are taken apart. According to Corne, the core of eCube’s business is disassembly of around 1,000-1,200 components off narrowbody aircraft and 1,500-2,000 components off widebody aircraft.

Trending Teardowns

Corne says that despite the grim terminology in the teardown industry, most of the aircraft eCube sees are midlife rather than “dead aircraft.” And, says Corne, the aircraft ages are beginning to trend even younger—with the company recently performing teardowns of Airbus A319s and Embraer E-Jets younger than ten years old. “Over the last couple of years, I would suggest that—irrespective of the type of aircraft—we’ve started to see a trend towards younger aircraft,” says Corne, adding that he thinks this may be driven by buyers of these aircraft wanting to get their hands on the engines, which may make it financially worth taking the entire aircraft out of operation.

Disassembling the Aircraft

For eCube, which runs seven disassembly lines across Europe, each aircraft disassembly is managed by a team of around 8-9 people, including technicians who perform the teardown and logistics workers who record data on each component. Once the components are off the aircraft, they will be securely wrapped or crated and made available for shipment worldwide. The entire process between disassembling the aircraft and getting components manifested, packaged and ready for shipment takes approximately five weeks.

High Value Components and Hazardous Materials

Since engines are the highest value components, they are removed first so customers are able to get value out of the aircraft as quickly as they can. Corne says this is followed by other high value areas, such as the APU, avionics bay and landing gears.

During the disassembly process, care must be taken in dealing with hazardous materials. In addition to draining hydraulic oil and fuels, disassembly specialists must treat components such as toilet tanks properly as a biohazard. Meanwhile, when shipping components considered to be dangerous goods—such as evacuation slides or oxygen tanks, which use compressed gas—eCube must package and ship them according to safety regulations.

The Fate of Unserviceable Components

If disassembled components are considered unserviceable, they are sent to end-of-life destruction facilities such as Conecsus Aerospace, which breaks them down into scrap material or mutilates them beyond reuse according to FAA regulations. “Once an MRO or a certified repair shop has determined that a part is no longer serviceable, it’s more of a liability for the owner of the asset to ensure that it’s not going to end up back on a plane it doesn’t need to be on in an unsafe manner,” explains Dawn Lassetter, vice president operations, Conecsus Aerospace.

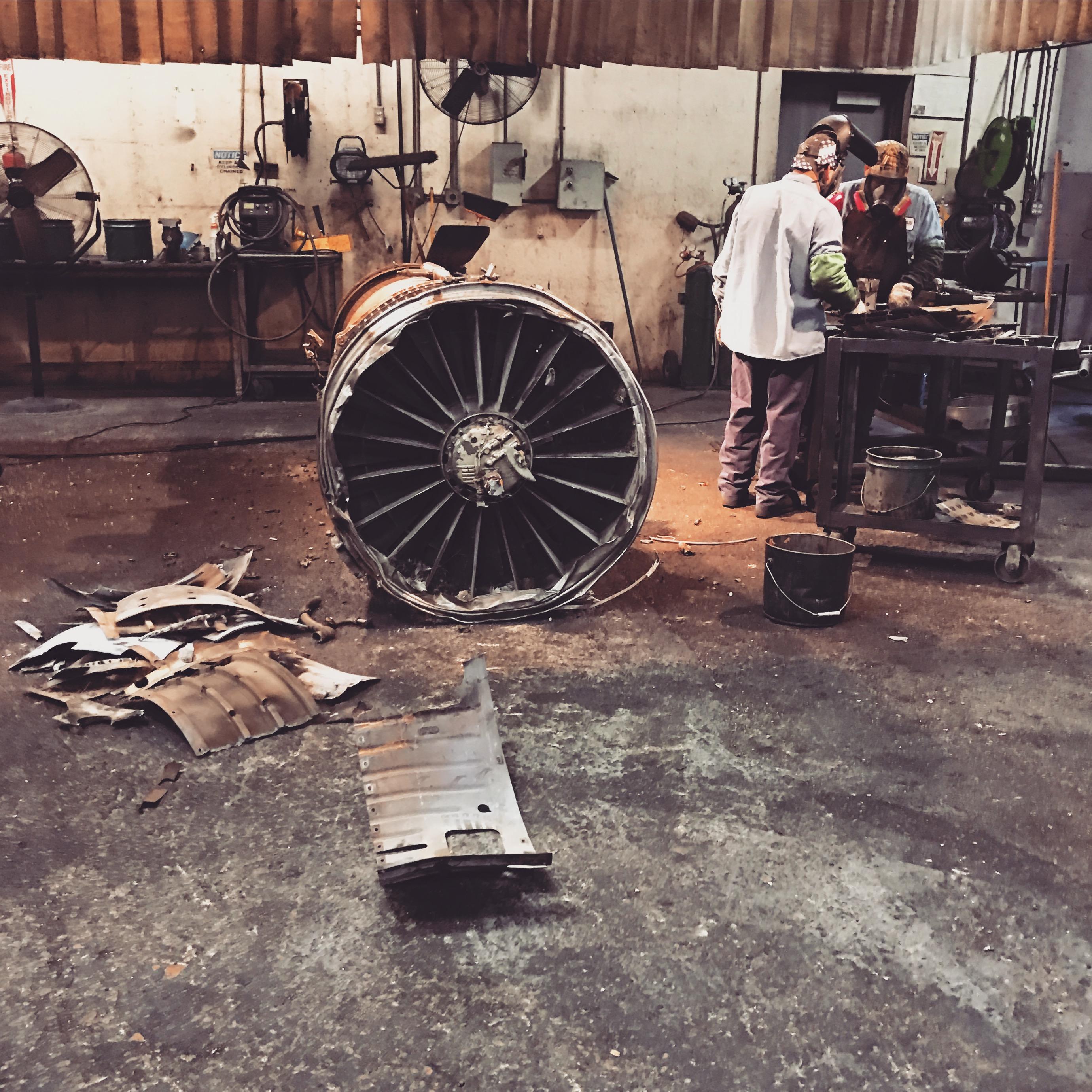

Certified Destruction Process

To ensure scrapped components are not reintroduced onto aircraft, they are taken apart and mutilated using tools such as grinders, saws, cutting torches and plasma cutters. “There’s nothing pretty about it—everything’s just mutilated,” says Lassetter, adding that how a component is mutilated and which parts are preserved depends on what type of alloy it is made of. “It’s kind of like playing a game of doctor. You just meticulously tear down this engine from a complete engine into all of its separate alloys, which are then sorted and offered out to the major refineries throughout the states that melt them into something else,” she explains.

“Parts-wise alone, there are hundreds if not more individual parts and pieces, and different metal and alloy types, so every piece of the cow gets used if looking at it from a butcher scenario,” adds Davin Gordon, vice president procurement, Conecsus Aerospace. “Everything is totally chopped up, split apart and put into its separate categories.”

Getting Value Out of Scrap

Because components such as turbine engines contain a variety of high value metals and alloys, end of life processing specialists like Mastermelt Alloy take great care to segregate and collect all of the material. “Our goal is to get the material down to the most virgin form of revert so that we can sell this material back to melt shops for future aerospace parts,” says Nathan Hymel, vice president alloys, Mastermelt.

Identifying Elements

“Our process begins by separating the scrap material and breaking it out by the different types of alloys using a handheld XRF analyzer,” says Hymel. “Next, we leach the material to take off coatings and brazings commonly found in the turbine engine,” which often consist of precious metals such as platinum, gold, palladium and silver. These metals are then processed into a marketable form such as powders or bars, which are then sold to make new precious metal bearing products.

Reusing Metals and Alloys

As for alloys, Mastermelt breaks them down by type, which in the aerospace industry generally means wrought alloys—which can be used to make HPT (high pressure turbine) and LPT (low pressure turbine) disks and gears—or cast alloys—which can be used to make new engine blades, vanes and shrouds. Stevan Curtis, national sales manager for Mastermelt, says the highest demand alloys they see in the marketplace are Inconel, Waspaloy, Renes and Hastelloy types, which are commonly found in the hot section of the engine. Curtis says this material is re-melted into new ingots for the aerospace industry.

Keeping It In The Industry

“Most of this material is part of our closed loop, allowing us to recycle the aerospace material and keep it in the aerospace community versus the material going out as a stainless-steel blind and finding its way into skyscrapers and bridges,” says Curtis. “Our materials are generally sold to companies making aerospace products for their customers.”

Environmental Benefits

One major environmental benefit of this process is that the industry is able to reuse elements that normally have to be mined. “We are finding alloys that are made of a number of natural elements and have to be blended or melted in order to make these specific alloys,” explains Hymel. “With our ability to verify the alloys, we reduce the emissions that we have to release for these special blends or melts requiring less emissions into the environment.” Hymel adds that the recycling process also keeps other materials such as plastics and rubber from going to landfills.

Aviation Versus Other Industries

eCube’s Corne agrees that the industry’s end of life process provides considerable environmental benefits. “In terms of environmental performance, if you try to measure it—or the incoming weight of the aircraft and how much of that is either reused or recycled—we are confident that we’ll always see 90% or more of the aircraft either reused or recycled by the weight of the material that came in,” he says. “We think by comparison to other industry sectors, the statistics associated with recycling aircraft are actually very positive.”

A behind the scenes look at how aircraft are taken apart and their raw materials are recycled into the aviation industry.