In Part 1, we discussed the classic simulator circling check and the “Part 142” excuse.

You might think the odds are stacked against us at a major international airport with multiple runways, but they are actually improved. These airports have full approach lighting systems that make keeping sight of the airport easier. Ironically, you will almost never have to circle at one of these airports, since they tend to have precision approaches to each runway. Where things become really hazardous is where you have just one, short runway.

I used to be based at Boire Field (KASH), New Hampshire, where the choices for the single runway were the ILS Runway 14 or the VOR Runway 32. If the ILS was down, our best option was said to be the VOR Runway 32, circle to Runway 14 with 2-sm minimum visibility.

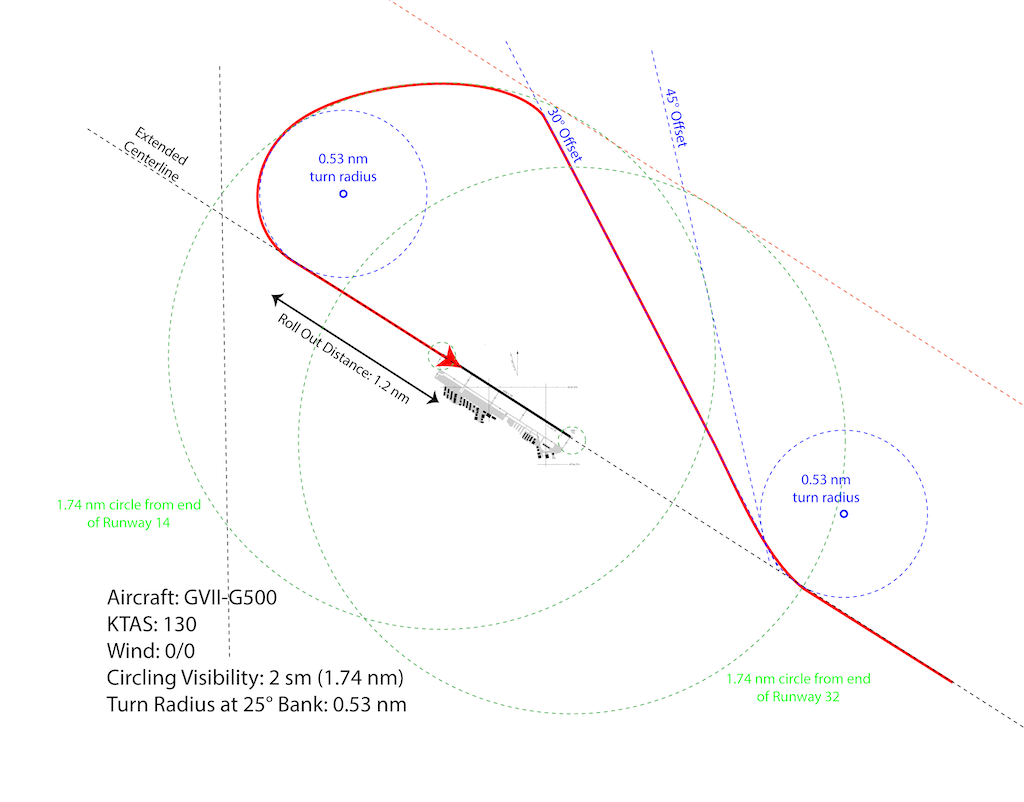

After flying simulated circling approaches with less visibility, I thought this would be easy. It was not: It left us rolling out just 1.2 nm from the touchdown zone. That comes to (1.2)(318) = 382 ft. The runway has since been lengthened, but back then it was 5,500 ft. long. We learned that given the choice of circling at minimums and landing someplace else, the someplace else was always a better option.

Creatively Extending Your Vision

Is this problem going to get better anytime soon? I doubt it. As disingenuous as the system is, we pilots are even more ingenious at finding ways to “creatively” extend our vision and our success in flying the unflyable.

Many aircraft, like mine, offer very good map displays of the runway environment with the aircraft’s position drawn in real time. We can size the display to draw a 2-nm circle around the aircraft as well as 2-nm “feathers” that depict localizer beams off any runways with an ILS approach. We are encouraged to do this as a way of improving our situational awareness.

I’ve seen more than a few pilots struggle with the KMEM Runway 27 circle to Runway 18R and then be given helpful hints on how to use this technology to improve their odds. We are told to place that circle over the ILS feather to Runway 27. Yes, that keeps you within 2 nm of the airport environment. But 2 nm converts to 2.3 sm and our visibility minimum is 1.5 sm. Somebody is cheating: Either the pilot doesn’t really see the airport, or the examiner has fudged with the visibility. No matter who is fudging, we pilots are taught we can safely circle at our visibility minimums. I contend that we cannot.

Solving the Circling Conundrum

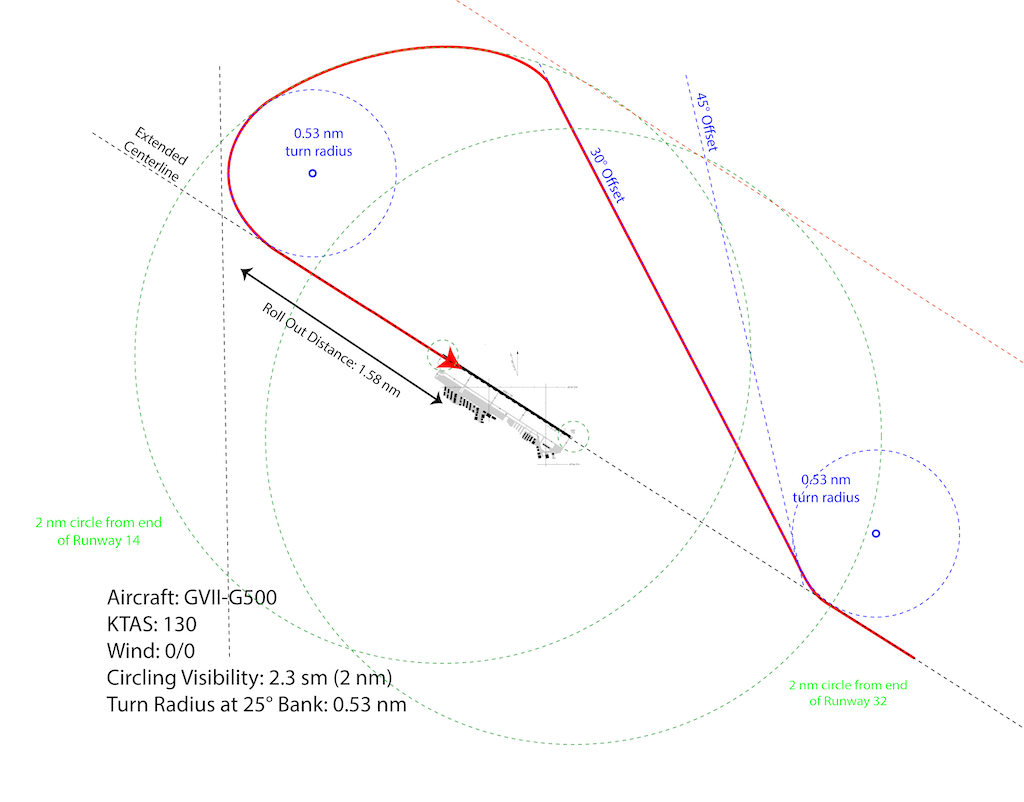

I often wonder about the fact that we use statute miles for visibility and nautical miles for everything else. Let’s say in our small airport example we insisted on our visibility minimums using the same numerical value, but in nautical miles. Would that extra 15% solve things? Yes, it appears it would. Being able to begin our offset earlier and fly a wider base turn allows us to roll out 1.58 nm from touchdown. That means we will be at (1.58)(318) = 502 ft. Again, that requires perfection from imperfect pilots. So this is hardly the solution to what ails us. But there are two better solutions available.

Solution One: Raise the visibility minimums. We are told repeatedly that “Circling is a VFR maneuver.” In my flight department, we require at least a 1,000-ft. ceiling and 3 sm visibility for circling. If we don’t have that, we look for another place to land.

RNAV Approach At Dekalb-Peachtree

Solution Two: Technology. We often fly to Dekalb-Peachtree Airport (KPDK), Georgia, where there are several instrument approaches available for landing on Runway 21L. As of the day I am writing this, we do not have our Letter of Authorization (LOA) to use the only approach available for the opposite runway, the RNAV (RNP) Runway 3R. (We applied more than six months ago.) We are fully trained, and our aircraft is fully capable. The RNAV (RNP) has turned circling, a very unsafe maneuver, into one of the easiest in the book. And easy means safe.

If the dangers of circling are as I’ve outlined them here, why do they persist? I believe they continue at many airports because they are an easy way of offloading the responsibilities of air traffic control onto the pilot. ATC will continue to use circling approaches if we pilots continue to accept them. We pilots will continue to accept them because our training tells us it is safe to do so. The approach visibility minimums have the FAA’s stamp of approval, after all. But keep in mind you can say the same thing about the once-ubiquitous non-directional beacon (NDB) approach.

Most of the airports I use have long ago decommissioned their NDB approaches, and to that I long ago said, “Good riddance!” I think few will argue with the idea that an NDB approach can be deadly. Now that we’ve slayed that dragon, it is time to aim for the next. I am hoping for the day circling approaches will be as rare as those awful NDB approaches. And on that day, I will once again say, “Good riddance!”

Circling Appproaches: Good Riddance! Part 1 https://aviationweek.com/business-aviation/safety-ops-regulation/circli…

Comments