Canada’s airlines are in a deep freeze. The government in Ottawa has dithered for a year now trying to decide whether to offer some sort of financial aid to the country’s airlines, and questions are beginning to arise as to whether Air Canada and WestJet, the two largest carriers, will be able to resume their roles as healthy global competitors post-pandemic.

Indecision ultimately can become a decision by default—largely doing nothing to help the country’s airlines while imposing some of the most stringent COVID-19 travel restrictions in the world has sent the country’s airlines into a state of despair. Canadian airline route network maps are filled with shocking patches of white. Many of the country’s airline employees are furloughed. The country requires both a negative COVID-19 test at the passenger’s expense and a mandated quarantine for passengers arriving in the country, and even discourages most domestic flying.

“Domestic and international travel restrictions and quarantines have caused demand to plummet," WestJet president and CEO Ed Sims said recently when announcing he had no other choice but slash more routes.

First, a word of praise for Canada and its government. Unlike the disastrous response in the US to COVID-19, which has led to more than half a million deaths and counting for Canada’s southern neighbor (the most of any country in the world), Prime Minister Justin Trudeau and Canada have weathered the pandemic relatively well.

With a population of 37 million people, Canada has had the 21st most deaths from COVID-19 in the world—more than 22,400. That equates to 543 deaths per million citizens, less than a third of the US rate of 1,646 deaths per million citizens. Canada has achieved this largely by hunkering down and, in particular, grinding its travel industry to a halt.

“We have to keep taking strong public health measures,” Trudeau said last week, noting the nation is endeavoring to ward off a third wave of COVID-19. This is all well and good: nothing is more important than saving lives. But it has come at a big cost to the country’s airlines.

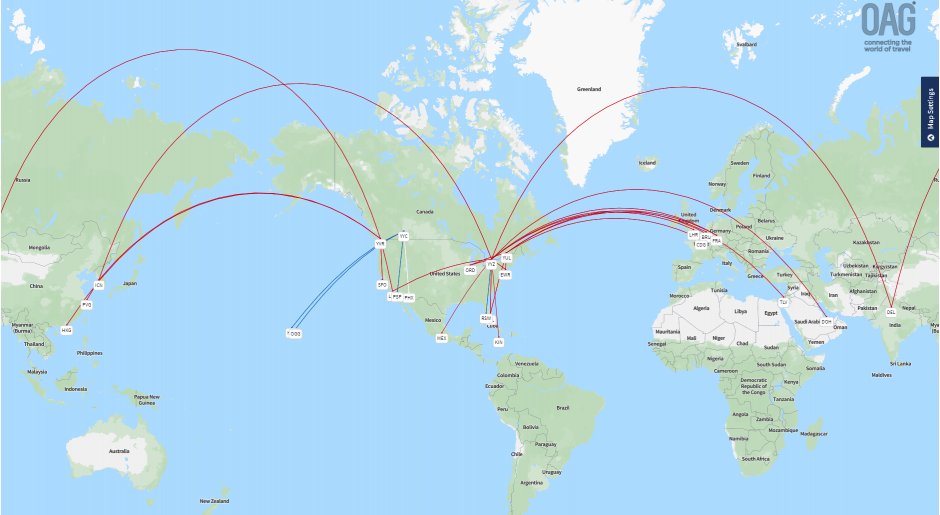

Air Canada (red) and WestJet (blue) are operating skeletal networks. Credit: OAG

A number of US airlines this week forecast improved bookings for spring and summer travel, driven by continued positive momentum in COVID-19 case counts and vaccinations, opening up the possibility that US airline networks could look closer to pre-pandemic levels as the year goes on.

Air Canada and WestJet spent years assiduously building themselves into truly global North American airlines. Prior to the pandemic, Air Canada was competing directly with US carriers for international passengers; Americans were increasingly willing to take a short flight across the border to Canadian hubs such as Toronto (YYZ) and Vancouver (YVR) to connect to Air Canada’s first-rate long-haul flights. WestJet, founded as an LCC in the 1990s, had in recent years shed its provincial beginnings to become a global operator flying Boeing 787s and entering into a partnership with US giant Delta Air Lines.

The North American airline market had become truly that—a continental market in which Air Canada, WestJet and, to the south of the US, Aeromexico were formidable competitors to the likes of Delta, American Airlines and United Airlines.

But with US airlines grinding through the pandemic and robust US government assistance allowing the country’s airline employees to remain employed, the US airline industry looks like it could reach something like normalcy by next year. Will Air Canada and WestJet be somewhat equal competitors to their US rivals as they were before the pandemic?

Right now, it appears as if the Canadian airlines will be, at best, playing catch up to the US counterparts for some time—if not becoming altogether uncompetitive and reverting to being less-than-truly-global carriers.

The US industry may be operating in slow motion—but that means it can pick up the pace as the pandemic recedes and be back to a full sprint when demand returns. Canada’s airlines, virtually at a standstill, are like track runners who will need to spend considerable time stretching and getting loose before rejoining the race. A largely grounded airline cannot just be restarted as one turns on a light switch.

Jerry Dias, the president of Unifor, Canada’s largest private sector union, made a desperate plea to Ottawa during a March 16 press conference. “Governments around the world acted swiftly to support their aviation sector. The government of Canada disturbingly stands alone when it comes to turning its back on aviation workers,” he said, adding: “We’ve worked with employers and experts to present sensible options for the government. One year of inaction is a shameful anniversary. What is the federal government waiting for?”

A country doesn’t have to have a globally competitive airline industry. American, Delta and United will be happy to accommodate Canadians willing to drive or fly across the border to access their global networks. Canada could decide that its airlines are better off simply focused on the Canadian domestic market with a small international footprint. But it doesn’t appear that Canada has decided anything regarding its airlines; indecision, however, could amount to a devastating de-facto “decision” for Canada’s airlines and airline workers.

Photo credit: Joe Pries